Originally appeared here:

Faster LLMs with speculative decoding and AWS Inferentia2

Go Here to Read this Fast! Faster LLMs with speculative decoding and AWS Inferentia2

Originally appeared here:

Faster LLMs with speculative decoding and AWS Inferentia2

Go Here to Read this Fast! Faster LLMs with speculative decoding and AWS Inferentia2

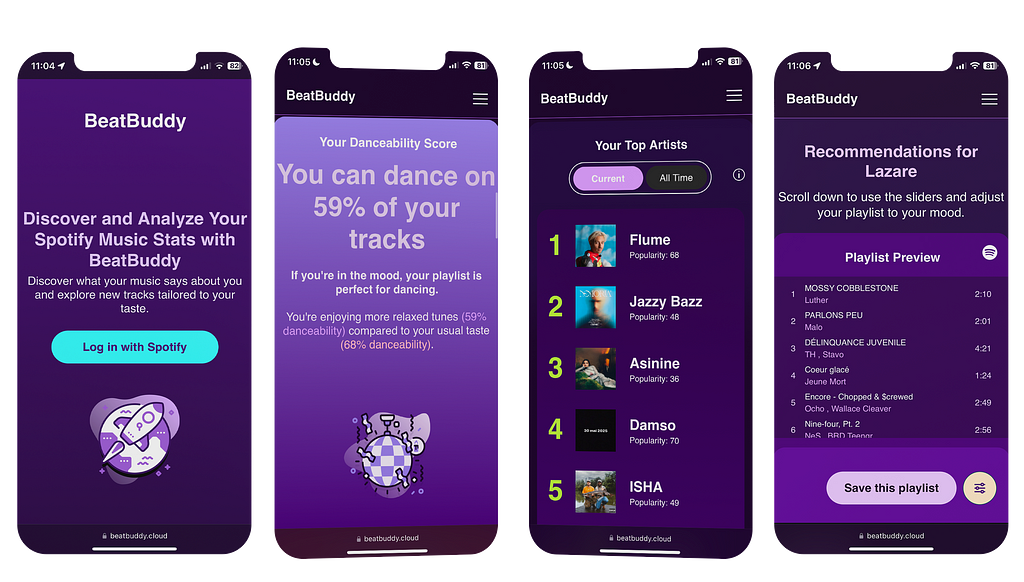

Hi there, and welcome to this article! I’m going to explain how I built BeatBuddy, a web app that analyzes what you’re listening to on Spotify. Inspired by Spotify Wrapped, it aims to interpret your current mood and provide recommendations that you can tweak based on that analysis.

If you don’t want to read everything and just want to give it a try, you can do so here: BeatBuddy. For the rest, keep reading!

I’m a data analyst and a music lover, and I believe that data analysis is a powerful way to understand the world we live in and who we are as individuals.

Music, in particular, can act as a mirror, reflecting your identity and emotions at a given moment. The type of music you choose often depends on your current activities and mood. For example, if you’re working out, you might choose an energetic playlist to motivate you.

On the other hand, if you are busy studying or focusing on crushing some data, you may want to listen to calm and peaceful music. I’ve even heard of people listening to white noise to focus, which can be described as the sound you hear when you open the windows of your car on the highway.

Another example of how music can reflect your mood is at a party. Imagine you are having a party with friends and you have to choose the music. If it’s a casual dinner, you might want to play some smooth jazz or mellow tunes. But if you’re aiming for the kind of party where everyone ends up dancing on the furniture or doing their best drunken karaoke performance of an ’80s hit, you’ll want to choose songs that are energetic and danceable. We’ll come back to these concepts in a moment.

In fact, all the music you listen to and the choices you make can reveal fascinating aspects of your personality and emotional state at any given moment. Nowadays, people tend to enjoy analytics about themselves, and it’s becoming a global trend! This trend is known as the “quantified self,” a movement where people use analytics to track their activities, such as fitness, sleep, and productivity, to make informed decisions (or not).

Don’t get me wrong, as a data nerd, I love all these things, but sometimes it goes too far — like with AI-connected toothbrushes. Firstly, I don’t need a toothbrush with a Wi-Fi antenna. Secondly, I don’t need a line chart showing the evolution of how well I’ve been brushing over the last six weeks.

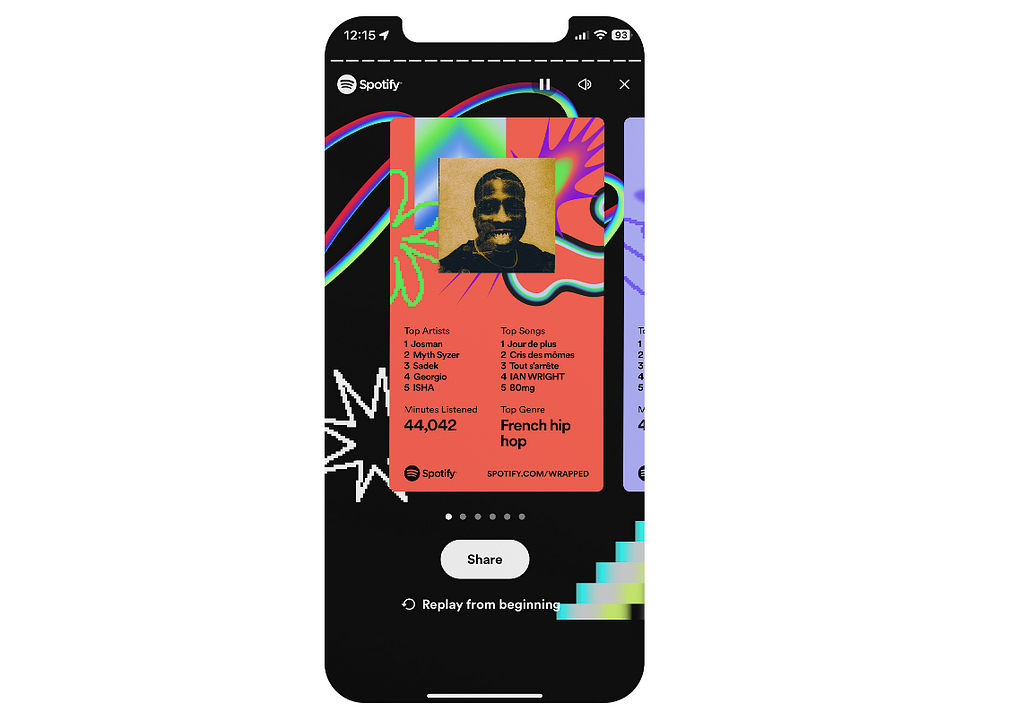

Anyway, back to the music industry. Spotify was one of the pioneers in turning user data collection into something cool, and they called it Spotify Wrapped.

At the end of the year, Spotify compiles what you’ve listened to and creates Spotify Wrapped, which goes viral on social media. Its popularity lies in its ability to reveal aspects of your personality and preferences that you can compare to your friends.

This concept of how Spotify collects and aggregates data for these year-end summaries has always fascinated me. I remember asking myself, “How do they do that?” and that curiosity was the starting point for this project.

Well, not exactly. Let’s be honest: The idea to analyze Spotify data was written on a note titled “data project”-you know, the kind of note filled with ideas you’ll probably never start or finish. It sat there for a year.

One day, I looked at the list again, and with a new confidence in my data analysis skills (thanks to a year of growth and improvements of ChatGPT), I decided to pick an item and start the project.

At first, I just wanted to access and analyze my Spotify data for no particular purpose. I was simply curious to see what I could do with it.

Starting a project like this, the first question you want to ask yourself is where the data source is and what data is available. Essentially, there are two ways to obtain your data:

Obviously, I went for the second option. To do so, you first need to create a developer project to get your API keys, and then you’re good to go.

Remember we talked about the fact that certain tracks are more likely danceable than others. As human beings, it’s quite easy to feel if a song is danceable or not — it’s all about what you feel in your body, right? But how do computers determine this?

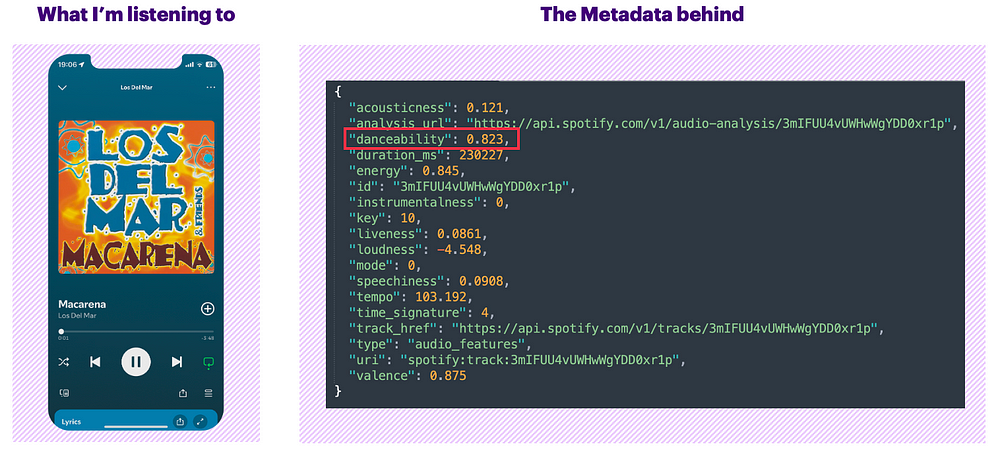

Spotify uses its own algorithms to analyze every song in its catalog. For every song, they provide a list of features associated with it. One use of this analysis is to create playlists and give you recommendations. The good news is that their API provides access to these analyses through the audio_features endpoint, allowing you to access all the features of any song.

For example, let’s analyze the audio features of the famous song “Macarena,” which I’m sure everyone knows. I won’t cover every parameter of the track in detail, but let’s focus on one aspect to better understand how it works — the danceability score of 0.823.

According to Spotify’s documentation, danceability describes how suitable a track is for dancing based on a combination of musical elements, including tempo, rhythm stability, beat strength, and overall regularity. A score of 0.0 is the least danceable, and 1.0 is the most danceable. With a score of 0.823 (or 82.3%), it’s easy to say that this track is very danceable.

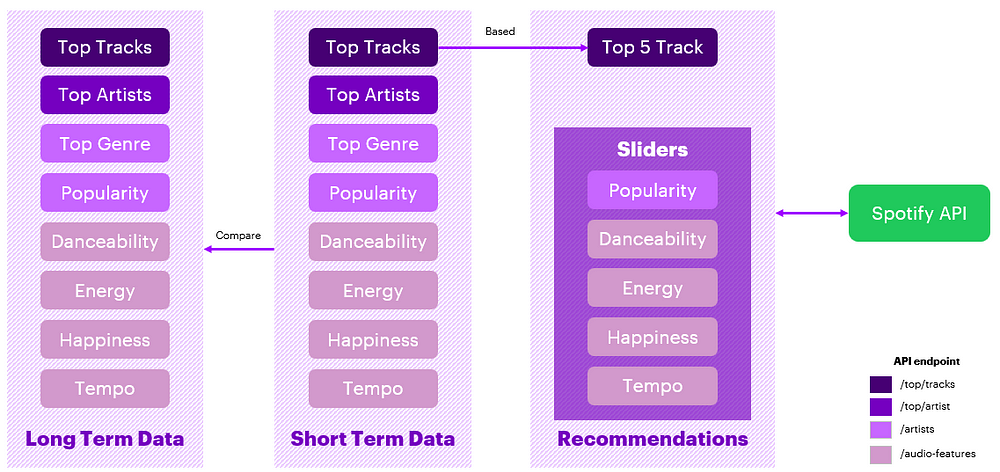

Before going further, I need to introduce a concept with the Spotify API called time_range. This interesting parameter allows you to retrieve data from different time periods by specifying the time_range:

Let’s illustrate this with an example: if you want to get your top 10 tracks from the last 4 weeks, you can call the corresponding endpoint and pass the time_range as a parameter like this : https://api.spotify.com/v1/me/top/artists?time_range=short_term&limit=10

Calling this will give you your top 10 artists from the past month.

With all this information available, my idea was to create a data product that allows users to understand what they are listening to, and to detect variations in their mood by comparing different temporalities. This analysis can then show how changes in our lives are reflected in our music choices.

For example, I recently started running again, and this change in my routine has affected my music preferences. I now listen to music that is faster and more energetic than what I typically listened to in the past. That’s my interpretation, of course, but it’s interesting to see how a change in my physical activity can affect what I listen to.

This is just one example, as everyone’s musical journey is unique and can be interpreted differently based on personal experiences and life changes. By analyzing these patterns, I think it is pretty cool to be able to make connections between our lifestyle choices and the music that we like to listen to.

The deeper I got into this project, the more I came to realize that, yes, I could analyze my data and come to certain conclusions myself, but I wanted everyone to do it.

To me, the simplest way to share data insights with non-technical people and make it so very accessible is not through a fancy BI dashboard. My idea was to create something universally accessible, which led me to develop a mobile-friendly web application that anyone could use.

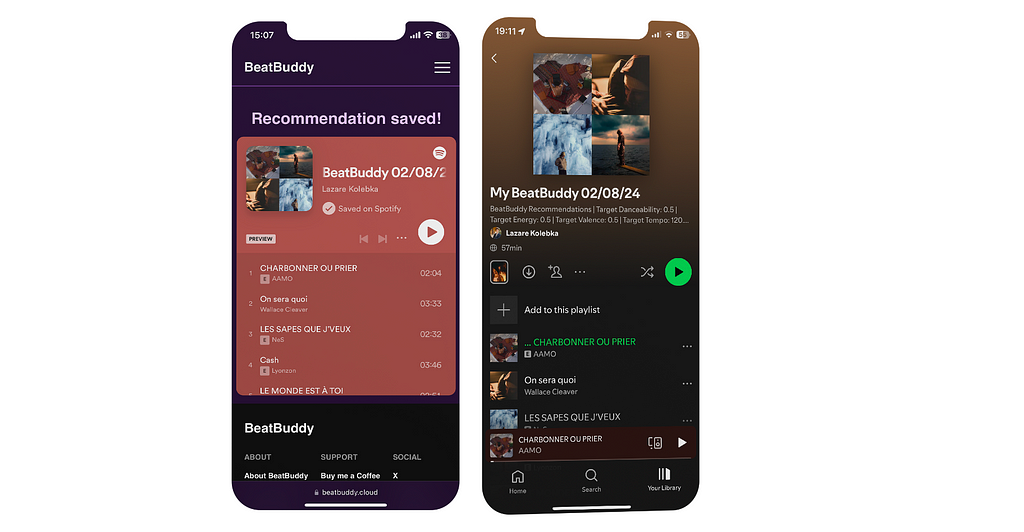

To use the app, all you need is a Spotify account, connect it to BeatBuddy with the click of one button, and you’re done !

Let’s look at another feature of the app: measuring the happiness level of the music you’re listening to, which could reflect your current mood. The app aggregates data from your recent top tracks, focusing on the ‘valence’ parameter, which represents musical happiness, with 1 being super happy music. For instance, if the average valence of your current tracks is 0.432, and your all-time average is 0.645, it might suggest a shift towards more melancholic music recently.

However, these analyses should be taken with a grain of salt, as these numbers represent trends rather than absolute truths. Sometimes, we shouldn’t always try to find a reason behind these numbers.

For example, if you were tracking your walking pace and discovered you have been walking faster lately, it doesn’t necessarily mean you’re in more of a hurry — it could be due to various minor factors like changes in weather, new shoes, or simply a subconscious shift. Sometimes changes occur without explicit reasons, and while it is possible to measure these variations, they do not always require straightforward explanations.

That being said, noticing significant changes in your music listening habits can be interesting. It can help you think about how your emotional state or life situation might be affecting your musical preferences. This aspect of BeatBuddy offers an interesting perspective, although it’s worth noting that these interpretations are only one piece of the complex puzzle of our emotions and experiences

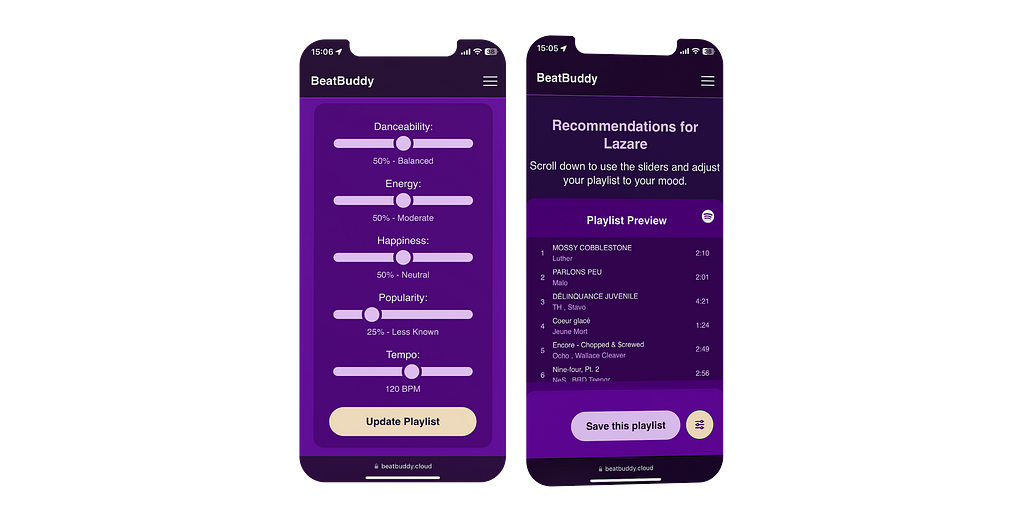

Let’s be honest, analyzing your listening habits is one thing, but how do you take action based on this analysis? In the end, making data-driven decisions is the ultimate goal of data analysis. This is where recommendations come into play.

An interesting feature of BeatBuddy is its ability to provide music recommendations based on a mood you select and the music you like.

For instance, you might realize that what you are listening to has a score of 75% popularity (which is quite high), and you want to find hidden gems tailored to your tastes. You can then tweak the “Popularity” slider to, say, 25% to create a fresh playlist with an average score of 25% popularity.

Behind the scenes, there’s an API call to Spotify’s algorithm to create a recommendation based on the criteria you’ve selected. This call generates a playlist recommendation tailored to both your personal tastes and the mood parameters you’ve set. It uses your top 5 recent tracks to fine-tune Spotify’s recommendation algorithm according to your choices.

Once you’re happy with the playlist, you can save it directly to your Spotify library. Each playlist comes with a description that details the parameters you chose, helping you remember the mood each playlist is meant to evoke.

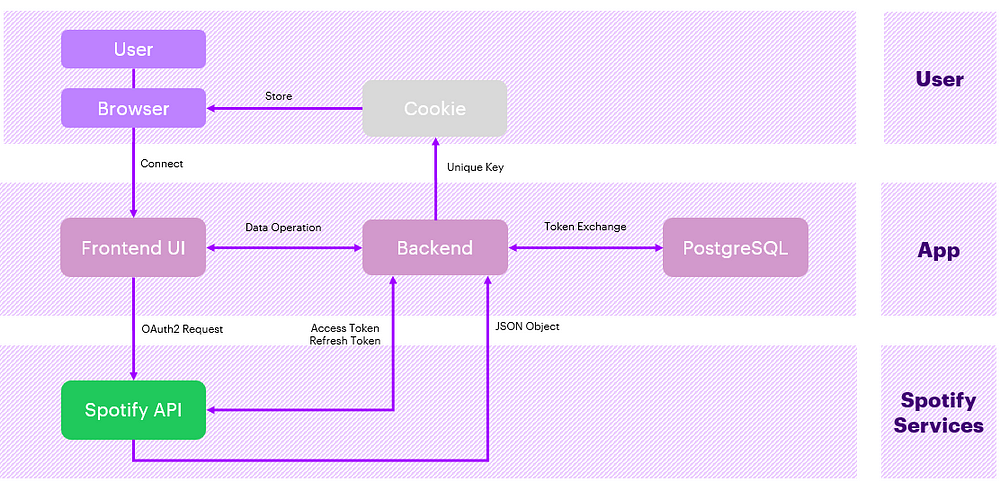

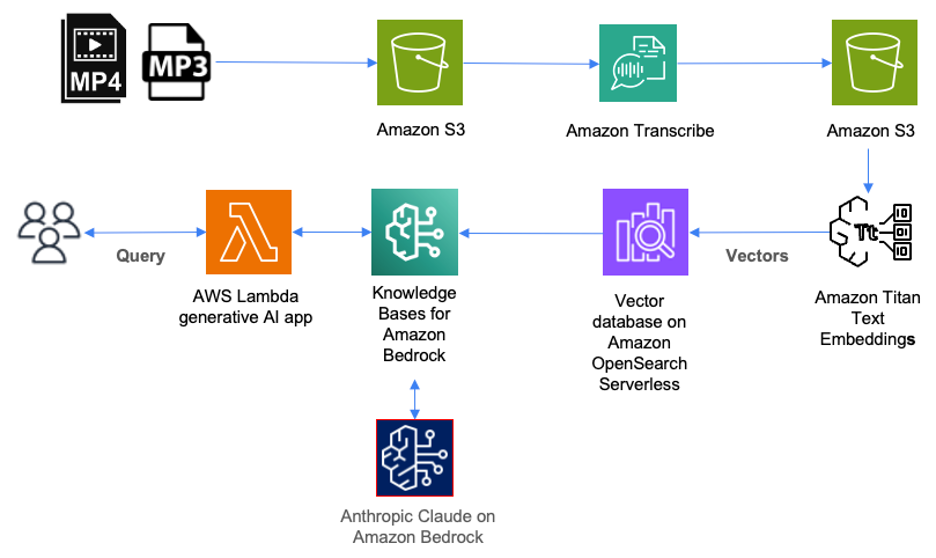

Developing a web application that analyzes Spotify data has been a challenging but rewarding journey. I have been pushed out of my comfort zone and gained knowledge in several areas, including web API, cookie management, web security, OAuth2, front-end development, mobile optimization, and SEO. Below is a diagram of the high-level architecture of the application:

My initial goal was to start a modest data project to analyze my listening habits. However, it turned into a three-month project rich in learning and discovery.

Throughout the process, I realized how closely related data analysis and web development are, especially when it comes to delivering a solution that is not only functional but also user-friendly and easily accessible. In the end, software development is essentially about moving data from one place to another.

One last note: I wanted to create an application that was clean and provided a seamless user experience. That is why BeatBuddy is completely ad-free, no data is sold or shared with any third parties. I’ve created this with the sole purpose of giving users a way to better understand their music choices and discover new tracks.

You can give the app a try here: https://www.beatbuddy.cloud

If you have any comments or suggestions, I’m all ears! Your feedback is really important.

For those interested in a deeper dive, keep an eye out for my upcoming article.

Cheers!

Lazare

How I Built BeatBuddy: A Web App that Analyzes Your Spotify Data was originally published in Towards Data Science on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Originally appeared here:

How I Built BeatBuddy: A Web App that Analyzes Your Spotify Data

Go Here to Read this Fast! How I Built BeatBuddy: A Web App that Analyzes Your Spotify Data

Ten Questions to test which AI assistant writes the best SQL

Originally appeared here:

ChatGPT vs. Claude vs. Gemini for Data Analysis (Part 1)

Go Here to Read this Fast! ChatGPT vs. Claude vs. Gemini for Data Analysis (Part 1)

You have probably seen AI generate images, such as these four corgis.

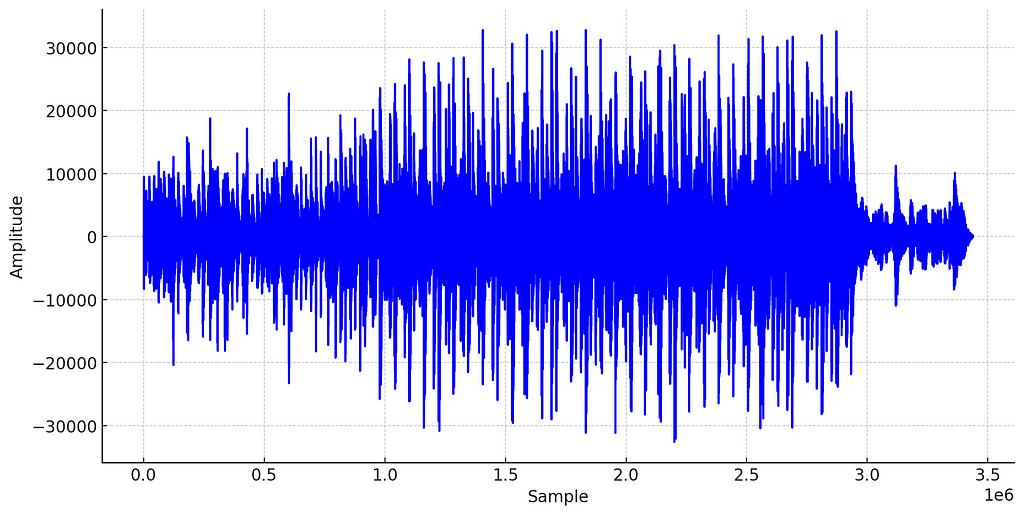

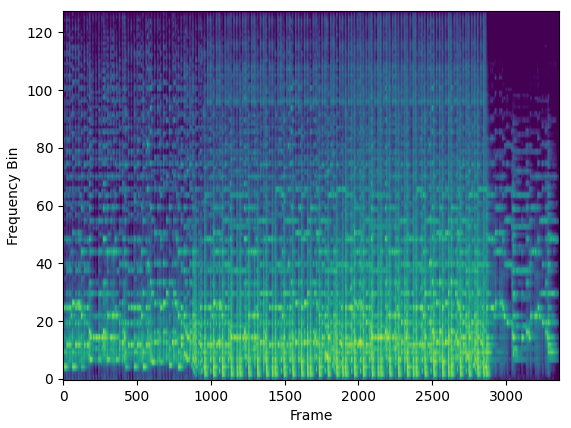

Maybe you have also seen AI generate sounds, such as these corgi barking sounds:

What if I told you these two generations are the exact same thing? Watch and listen for yourself!

Now, you might be confused about what I mean when I say “they are the same thing”. But do not worry; you will soon understand!

In May 2024, three researchers from the University of Michigan released a paper titled“Images that Sound: Composing Images and Sounds on a Single Canvas”.

In this post, I will explain

To answer this question, we need to understand two terms:

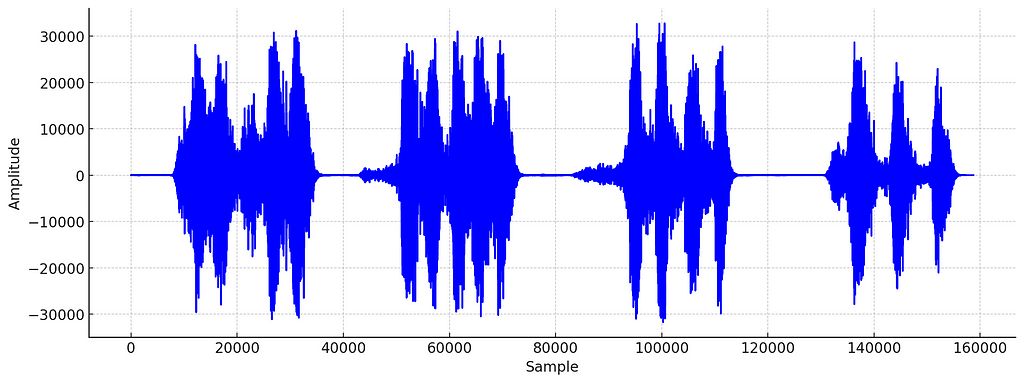

In the real world, sound is produced by vibrating objects creating acoustic waves (changes in air pressure over time). When sound is captured through a microphone or generated by a digital synthesizer, we can represent this sound wave as a waveform:

The waveform is useful for recording and playing audio, but it is typically avoided for music analysis or machine learning with audio data. Instead, a much more informative representation of the signal, the spectrogram, is used.

The spectrogram tells us which frequencies are more or less pronounced in the sound across time. However, for this article, the key thing to note is that a spectrogram is an image. And with that, we come full circle.

When generating the corgi sound and image above, the AI creates a sound that, when transformed into a spectrogram, looks like a corgi.

This means that the output of this AI is both sound and image at the same time.

Even though you now understand what is meant by an image that sounds, you might still wonder how this is even possible. How does the AI know which sound would produce the desired image? After all, the waveform of the corgi sound looks nothing like a corgi.

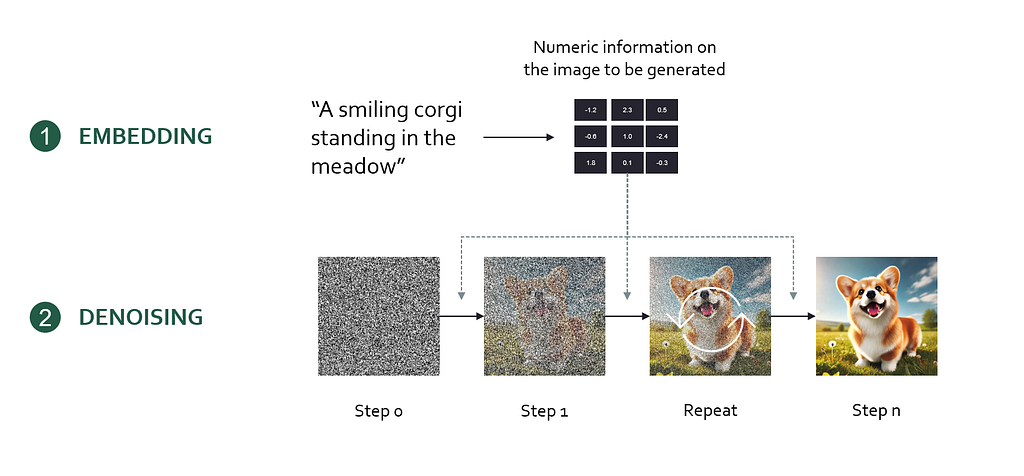

First, we need to understand one foundational concept: Diffusion models. Diffusion models are the technology behind image models like DALL-E 3 or Midjourney. In essence, a diffusion model encodes a user prompt into a mathematical representation (an embedding) which is then used to generate the desired output image step-by-step from random noise.

Here’s the workflow of creating images with a diffusion model

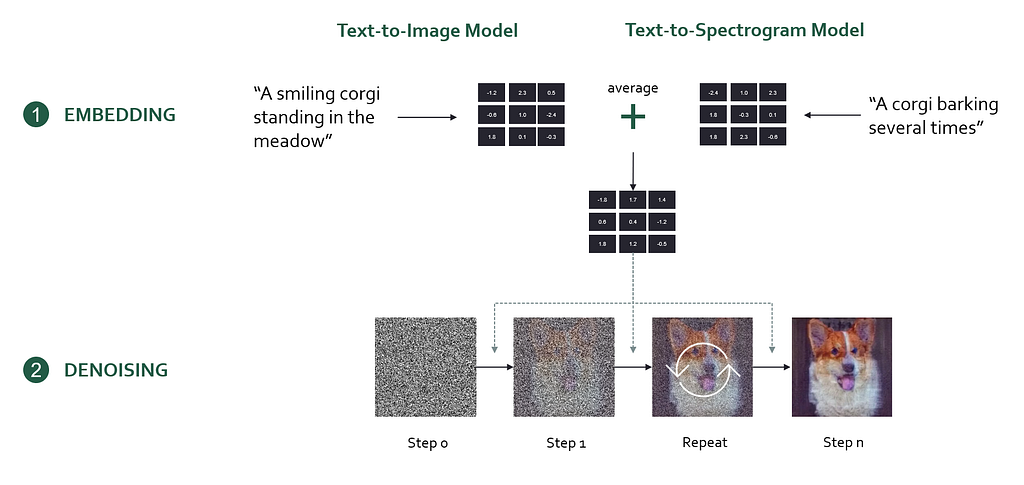

To generate “images that sound”, the researchers used a clever technique by combining two diffusion models into one. One of the diffusion models is a text-to-image model (Stable Diffusion), and the other is a text-to-spectrogram model (Auffusion). Each of these models receives its own prompt, which is encoded into an embedding and determines its own denoising instruction.

However, multiple different denoising instructions are problematic, because the model needs to decide how to denoise the image. In the paper, the authors solve this problem by averaging the denoising instructions from both prompts, effectively guiding the model to optimize for both prompts equally.

On a high level, you can think of this as ensuring the resulting image reflects both the image and audio prompt equally well. One downside of this is that the output will always be a mix of the two and not every sound or image coming out of the model will look/sound great. This inherent tradeoff significantly limits the model’s output quality.

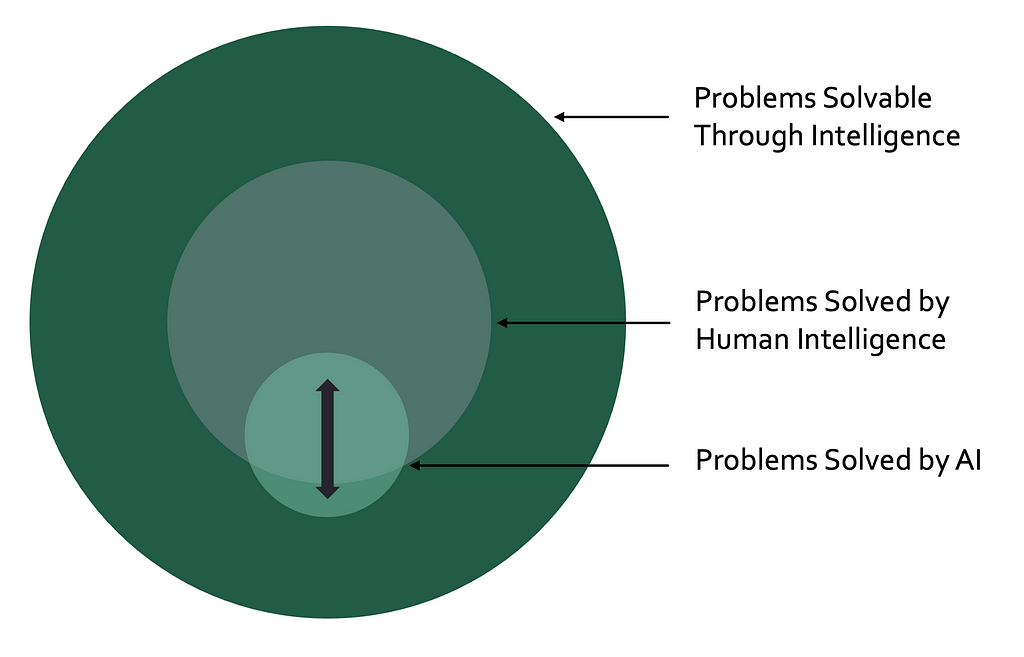

AI is commonly defined as computer systems mimicking human intelligence (e.g. IMB, TechTarget, Coursera). This definition works well for sales forecasting, image classification, and text generation AI models. However, it comes with the inherent restriction that a computer system can only be an AI if it performs a task that humans have historically solved.

In the real world, there exist a high (likely infinite) number of problems solvable through intelligence. While human intelligence has cracked some of these problems, most remain unsolved. Among these unsolved problems, some are known (e.g. curing cancer, quantum computing, the nature of consciousness) and others are unknown. If your goal is to tackle these unsolved problems, mimicking human intelligence does not appear to be an optimal strategy.

Following the definition above, a computer system that discovers a cure for cancer without mimicking human intelligence would not be considered AI. This is clearly counterintuitive and counterproductive. I do not intend to start a debate on “the one and only definition”. Instead, I want to emphasize that AI is much more than an automation tool for human intelligence. It has the potential to solve problems that we did not even know existed.

In an article on Mixmag, Becky Buckle explores the “history of artists concealing visuals within the waveforms of their music”. One impressive example of human spectrogram art is the song “∆Mᵢ⁻¹=−α ∑ Dᵢ[η][ ∑ Fjᵢ[η−1]+Fextᵢ [η⁻¹]]” by the British musician Aphex Twin.

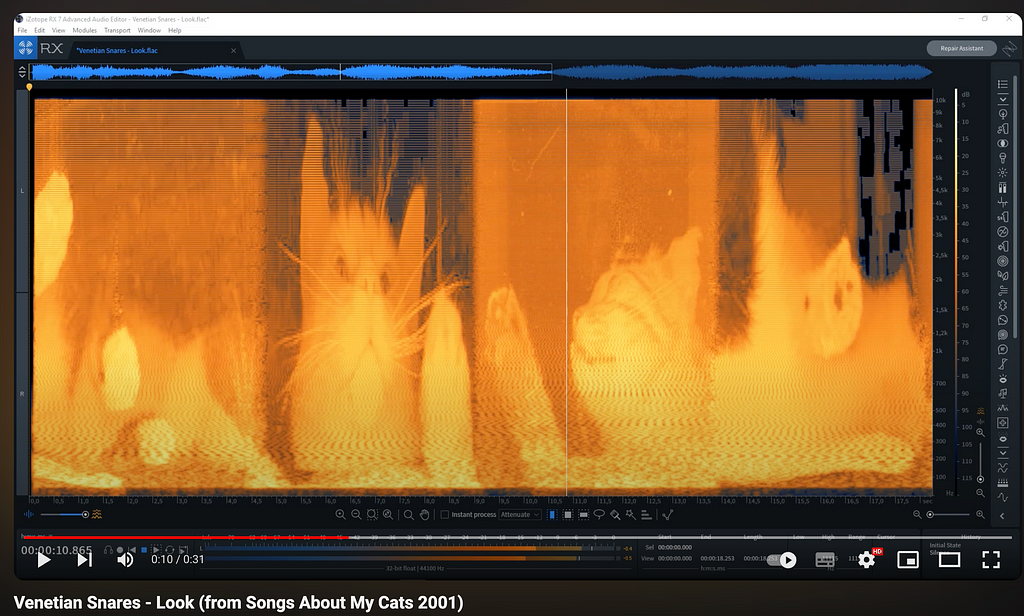

Another example is the track “Look” from the album “Songs about my Cats” by the Canadian musician Venetian Snares.

While both examples show that humans can encode images into waveforms, there is a clear difference to what “Images that Sound” is capable of.

If you listen to the above examples of human spectrogram art, you will notice that they sound like noise. For an alien face, this might be a suitable musical underscore. However, listening to the cat example, there seems to be no intentional relationship between the sounds and the spectrogram image. Human composers were able to generate waveforms that look like a certain thing when transformed to a spectrogram. However, to my knowledge, no human has been able to produce examples where the sound and images match, according to predefined criteria.

“Images that Sound” can produce audio that sounds like a cat and looks like a cat. It can also produce audio that sounds like a spaceship and looks like a dolphin. It is capable of producing intentional associations between the sound and image representation of the audio signal. In this regard, the AI exhibits non-human intelligence.

In recent years, AI has mostly been portrayed as a productivity tool that can enhance economic outputs through automation. While most would agree that this is highly desirable to some extent, others feel threatened by this perspective on the future. After all, if AI keeps taking away work from humans, it might end up replacing the work we love doing. Hence, our lives could become more productive, but less meaningful.

“Images that Sound” contrasts this perspective and is a prime example of beautiful AI art. This work is not driven by an economic problem but by curiosity and creativity. It is unlikely that there will ever by an economic use case for this technology, although we should never say never…

From all the people I’ve talked to about AI, artists tend to be the most negative about AI. This is backed up by a recent study from the German GEMA, showing that over 60% of musicians “believe that the risks of AI use outweigh its potential opportunities” and that only 11% “believe that the opportunities outweigh the risks”.

More works similar to this paper could help artists understand that AI has the potential to bring more beautiful art into the world and that this does not have to happen at the cost of human creators.

Images that Sound has not been the first use case of AI that has the potential to create beautiful art. In this section, I want to showcase a few other approaches that will hopefully inspire you and make you think differently about AI.

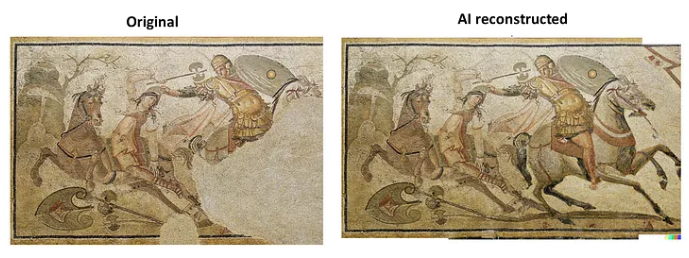

AI helps restore art by repairing damaged pieces precisely, ensuring historical works last longer. This mix of technology and creativity keeps our artistic heritage alive for future generations. Read more.

AI can animate photos to create realistic videos with natural movements and lip-syncing. This can make historical figures or artworks like the Mona Lisa move and speak (or rap). While this technology is certainly dangerous in the context of deep fakes, applied to historical portraits, it can create funny and/or meaningful art. Read more.

AI has the potential to enhance old recordings by transforming their mono mix into a stereo mix. There are classical algorithmic approaches for this, but AI promises to make artificial stereo mixes sound more and more realistic. Read more here and here.

Images that Sound is one of my favorite papers of 2024. It uses advanced AI training techniques to achieve a purely artistic outcome that creates a new audiovisual art form. What is most fascinating is that this art form exists outside of human capabilities, as of this day. We can learn from this paper that AI is not barely a set of automation tools that mimick human behavior. Instead, AI can enrich the aesthetic experiences of our lives by enhancing existing art or creating entirely novel works and art forms. We are only starting to see the beginnings of the AI revolution and I cannot wait to shape and experience its (artistic) consequences.

I’m a musicologist and a data scientist, sharing my thoughts on current topics in AI & music. Here is some of my previous work related to this article:

Find me on Medium and Linkedin!

Images that Sound: Creating Stunning Audiovisual Art with AI was originally published in Towards Data Science on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Originally appeared here:

Images that Sound: Creating Stunning Audiovisual Art with AI

Go Here to Read this Fast! Images that Sound: Creating Stunning Audiovisual Art with AI

The AI landscape is rapidly evolving, with synthetic data emerging as a powerful tool for model development. While it offers immense potential, recent concerns about model collapse have sparked debate. Let’s dive into the reality of synthetic data use and its impact on AI development.

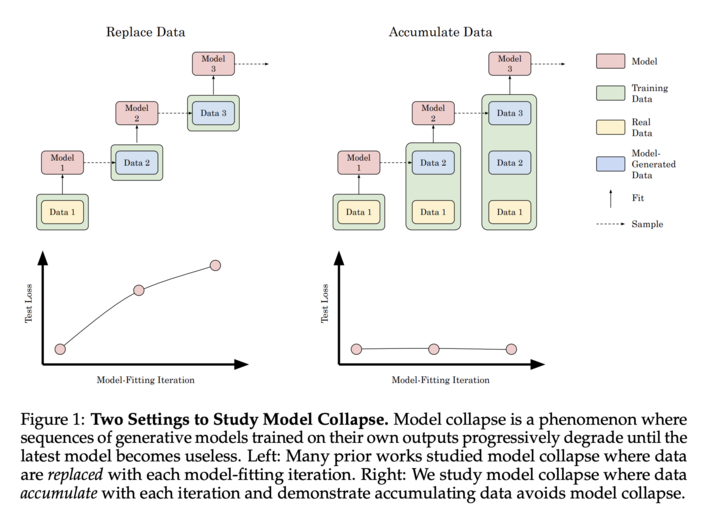

The Nature paper “AI models collapse when trained on recursively generated data” by Shumailov et al. raised important questions about the use of synthetic data:

However, it’s essential to note that this extreme scenario of recursive training on purely synthetic data is not representative of real-world AI development practices. The authors themselves acknowledge:

Supporting Quotes from the Paper

In practice, the goal of synthetic data is to augment and extend the existing datasets, including the implicit data baked into base models. When teams are fine-tuning or continuing pre-training, the objective is to provide additional data to improve the model’s robustness and performance.

The paper“Is Model Collapse Inevitable? Breaking the Curse of Recursion by Accumulating Real and Synthetic Data” by Gerstgrasser et al., researchers from Stanford, MIT, and Constellation presents significant counterpoints to concerns about AI model collapse:

This work has shown that combining synthetic data with real-world data can prevent model degradation.

Quality Over Quantity

As highlighted in Microsoft’s Phi-3 technical report:

This emphasizes the importance of thoughtful synthetic data generation rather than indiscriminate use.

And Apple in training their new device and foundation models:

This emphasizes the importance of thoughtful synthetic data generation rather than indiscriminate use.

Iterative Improvement, Not Recursive Training

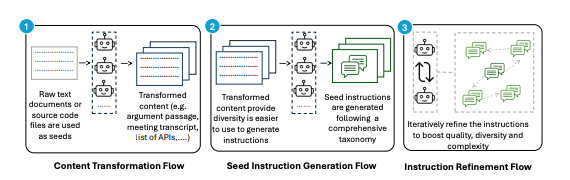

As highlighted in Gretel Navigator, NVIDIA’s Nemotron, and the AgentInstruct architecture, cutting edge synthetic data is generated by agents iteratively simulating, evaluating, and improving outputs- not simply recursively training on their own output. Below is an example of syntheticexample synthetic data generation architecture used in AgentInstruct.

Here are some example results from recent synthetic data releases:

Synthetic data is driving significant advancements across various industries:

Healthcare: Rhys Parker, Chief Clinical Officer at SA Health, stated:

“Our synthetic data approach with Gretel has transformed how we handle sensitive patient information. Data requests that previously took months or years are now achievable in days. This isn’t just a technological advance; it’s a fundamental shift in managing health data that significantly improves patient care while ensuring privacy. We predict synthetic data will become routine in medical research within the next few years, opening new frontiers in healthcare innovation.” [9]

Mathematical Reasoning: DeepMind’s AlphaProof and AlphaGeometry 2 systems,

“AlphaGeometry 2, based on Gemini and trained with an order of magnitude more data than its predecessor”, achieved a silver-medal level at the International Mathematical Olympiad by solving complex mathematical problems, demonstrating the power of synthetic data in enhancing AI capabilities in specialized fields [5].

Life Sciences Research: Nvidia’s research team reported:

“Synthetic data also provides an ethical alternative to using sensitive patient data, which helps with education and training without compromising patient privacy” [4]

One of the most powerful aspects of synthetic data is its potential to level the playing field in AI development.

Empowering Data-Poor Industries: Empowering Data-Poor Industries: Synthetic data allows industries with limited access to large datasets to compete in AI development. This is particularly crucial for sectors where data collection is challenging due to privacy concerns or resource limitations.

Customization at Scale: Even large tech companies are leveraging synthetic data for customization. Microsoft’s research on the Phi-3 model demonstrates how synthetic data can be used to create highly specialized models:

“We speculate that the creation of synthetic datasets will become, in the near future, an important technical skill and a central topic of research in AI.” [3]

Tailored Learning for AI Models: Andrej Karpathy, former Director of AI at Tesla, suggests a future where we create custom “textbooks” for teaching language models:

Scaling Up with Synthetic Data: Jim Fan, an AI researcher, highlights the potential of synthetic data to provide the next frontier of training data:

Fan also points out that embodied agents, such as robots like Tesla’s Optimus, could be a significant source of synthetic data if simulated at scale.

The Hugging Face blog shows that fine-tuning a custom small language model using synthetic data costs around $2.7 to fine-tune, compared to $3,061 with GPT-4 on real-world data, while emitting significantly less CO2 and offering faster inference speeds.

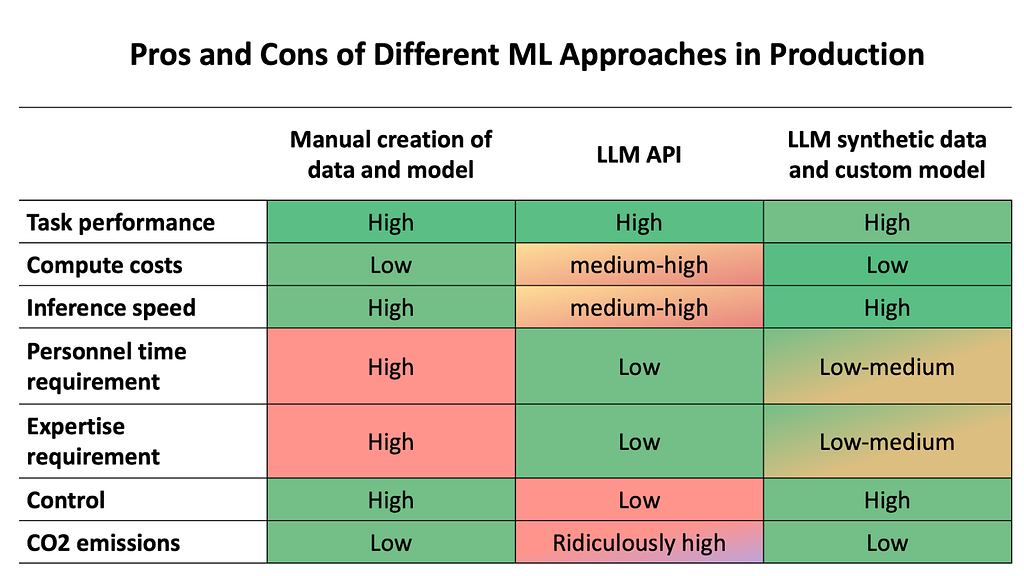

Here’s a nice visualization from Hugging Face that shows the benefits across use cases:

While the potential risks of model collapse should not be ignored, the real-world applications and benefits of synthetic data are too significant to dismiss. As we continue to advance in this field, a balanced approach that combines synthetic data with rigorous real-world validation and thoughtful generation practices will be key to maximize its potential.

Synthetic data, when used responsibly and in conjunction with real-world data, has the potential to dramatically accelerate AI development across all sectors. It’s not about replacing real data, but augmenting and extending our capabilities in ways we’re only beginning to explore. By enhancing datasets with synthetic data, we can fill critical data gaps, address biases, and create more robust models.

By leveraging synthetic data responsibly, we can democratize AI development, drive innovation in data-poor sectors, and push the boundaries of what’s possible in machine learning — all while maintaining the integrity and reliability of our AI systems.

Addressing Concerns of Model Collapse from Synthetic Data in AI was originally published in Towards Data Science on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Originally appeared here:

Addressing Concerns of Model Collapse from Synthetic Data in AI

Go Here to Read this Fast! Addressing Concerns of Model Collapse from Synthetic Data in AI

A full breakdown of how you can learn AI this year effectively

Originally appeared here:

How I’d Learn AI (If I Could Start Over)

Go Here to Read this Fast! How I’d Learn AI (If I Could Start Over)

Originally appeared here:

Catalog, query, and search audio programs with Amazon Transcribe and Knowledge Bases for Amazon Bedrock

Inspired by Andrej Kapathy’s recent youtube video on Let’s reproduce GPT-2 (124M), I’d like to rebuild it with most of the training optimizations in Jax. Jax is built for highly efficient computation speed, and it is quite interesting to compare Pytorch with its recent training optimization, and Jax with its related libraries like Flax (Layers API for neural network training for Jax)and Optax (a gradient processing and optimization library for JAX). We will quickly learn what is Jax, and rebuild the GPT with Jax. In the end, we will compare the token/sec with multiGPU training between Pytorch and Jax!

Based on its readthedoc, JAX is a Python library for accelerator-oriented array computation and program transformation, designed for high-performance numerical computing and large-scale machine learning. I would like to introduce JAX with its name. While someone calls it Just Another XLA (Accelerated Linear Algibra), I prefer to call it J(it) A(utograd) X(LA) to demonstrate its capability of high efficiency.

J — Just-in-time (JIT) Compilation. When you run your python function, Jax converts it into a primitive set of operation called Jaxpr. Then the Jaxpr expression will be converted into an input for XLA, which compiles the lower-level scripts to produce an optimized exutable for target device (CPU, GPU or TPU).

A — Autograd. Computing gradients is a critical part of modern machine learning methods, and you can just call jax.grad() to get gradients which enables you to optimize the models.

X — XLA. This is a open-source machine learning compiler for CPU, GPU and ML accelerators. In general, XLA performs several built-in optimization and analysis passes on the StableHLO graph, then sends the HLO computation to a backend for further HLO-level optimizations. The backend then performs target-specific code generation.

Those are just some key features of JAX, but it also has many user friendly numpy-like APIs in jax.numpy , and automatic vectorization with jax.vmap , and parallize your codes into multiple devices via jax.pmap . We will cover more Jax concepts nd applications in the futher blogs, but now let’s reproduct the NanoGPT with Jax!

GPT is a decoder-only transformer model, and the key building block is Attention module. We can first define a model config dataclass to save the model hyperparameters of the model, so that the model module can consume it efficiently to initialize the model architecture. Similar to the 124M GPT model, here we initialize a 12-layer transformer decoder with 12 heads and vocab size as 50257 tokens, each of which has 768 embedding dimension. The block size for the attention calculation is 1024.

from dataclasses import dataclass

@dataclass

class ModelConfig:

vocab_size: int = 50257

n_head: int = 12

n_embd: int = 768

block_size: int = 1024

n_layer: int = 12

dropout_rate: float = 0.1

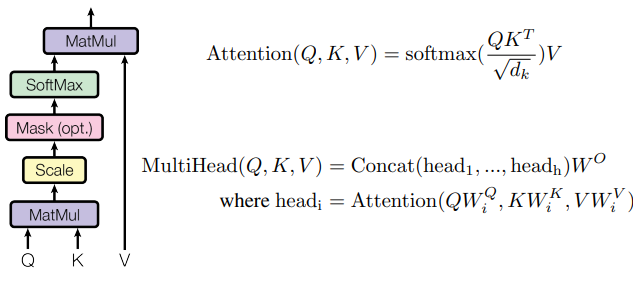

Next comes to the key building block of the transformer model — Attention. The idea is to process the inputs into three weight matrics: Key, Query, and Value. Here we rely on the flax , a the Jax Layer and training API library to initialize the 3 weight matrix, by just call the flax.linen.Dense . As mentioned, Jax has many numpy-like APIs, so we reshape the outputs after the weight matrix with jax.numpy.reshape from [batch_size, sequence_length, embedding_dim] to [batch_size, sequence_length, num_head, embedding_dim / num_head]. Since we need to do matrix multiplication on the key and value matrics, jax also has jax.numpy.matmul API and jax.numpy.transpose (transpose the key matrix for multiplication).

Note that we need to put a mask on the attention matrix to avoid information leakage (prevent the previous tokens to have access to the later tokens), jax.numpy.tril helps build a lower triangle array, and jax.numpy.where can fill the infinite number for us to get 0 after softmax jax.nn.softmax . The full codes of multihead attention can be found below.

from flax import linen as nn

import jax.numpy as jnp

class CausalSelfAttention(nn.Module):

config: ModelConfig

@nn.compact

def __call__(self, x, deterministic=True):

assert len(x.shape) == 3

b, l, d = x.shape

q = nn.Dense(self.config.n_embd)(x)

k = nn.Dense(self.config.n_embd)(x)

v = nn.Dense(self.config.n_embd)(x)

# q*k / sqrt(dim) -> softmax -> @v

q = jnp.reshape(q, (b, l, d//self.config.n_head , self.config.n_head))

k = jnp.reshape(k, (b, l, d//self.config.n_head , self.config.n_head))

v = jnp.reshape(v, (b, l, d//self.config.n_head , self.config.n_head))

norm = jnp.sqrt(list(jnp.shape(k))[-1])

attn = jnp.matmul(q,jnp.transpose(k, (0,1,3,2))) / norm

mask = jnp.tril(attn)

attn = jnp.where(mask[:,:,:l,:l], attn, float("-inf"))

probs = jax.nn.softmax(attn, axis=-1)

y = jnp.matmul(probs, v)

y = jnp.reshape(y, (b,l,d))

y = nn.Dense(self.config.n_embd)(y)

return y

You may notice that there is no __init__ or forward methods as you can see in the pytorch. This is the special thing for jax, where you can explicitly define the layers with setup methods, or implicitly define them withn the forward pass by adding nn.compact on top of __call__ method. [ref]

Next let’s build the MLP and Block layer, which includes Dense layer, Gelu activation function, LayerNorm and Dropout. Again flax.linen has the layer APIs to help us build the module. Note that we will pass a deterministic boolean variable to control different behaviors during training or evaluation for some layers like Dropout.

class MLP(nn.Module):

config: ModelConfig

@nn.compact

def __call__(self, x, deterministic=True):

x = nn.Dense(self.config.n_embd*4)(x)

x = nn.gelu(x, approximate=True)

x = nn.Dropout(rate=self.config.dropout_rate)(x, deterministic=deterministic)

x = nn.Dense(self.config.n_embd)(x)

x = nn.Dropout(rate=self.config.dropout_rate)(x, deterministic=deterministic)

return x

class Block(nn.Module):

config: ModelConfig

@nn.compact

def __call__(self, x):

x = nn.LayerNorm()(x)

x = x + CausalSelfAttention(self.config)(x)

x = nn.LayerNorm()(x)

x = x + MLP(self.config)(x)

return x

Now Let’s use the above blocks to build the NanoGPT:

Given the inputs of a sequence token ids, we use the flax.linen.Embed layer to get position embeddings and token embeddings. Them we pass them into the Block module N times, where N is number of the layers defined in the Model Config. In the end, we map the outputs from the last Block into the probabilities for each token in the vocab to predict the next token. Besides the forward __call__ method, let’s also create a init methods to get the dummy inputs to get the model’s parameters.

class GPT(nn.Module):

config: ModelConfig

@nn.compact

def __call__(self, x, deterministic=False):

B, T = x.shape

assert T <= self.config.block_size

pos = jnp.arange(0, T)[None]

pos_emb = nn.Embed(self.config.block_size, self.config.n_embd)(pos)

wte = nn.Embed(self.config.vocab_size, self.config.n_embd)

tok_emb = wte(x)

x = tok_emb + pos_emb

for _ in range(self.config.n_layer):

x = Block(self.config)(x)

x = nn.LayerNorm()(x)

logits = nn.Dense(config.n_embd, config.vocab_size)

# logits = wte.attend(x) # parameter sharing

return logits

def init(self, rng):

tokens = jnp.zeros((1, self.config.block_size), dtype=jnp.uint16)

params = jax.jit(super().init, static_argnums=(2,))(rng, tokens, True)

return params

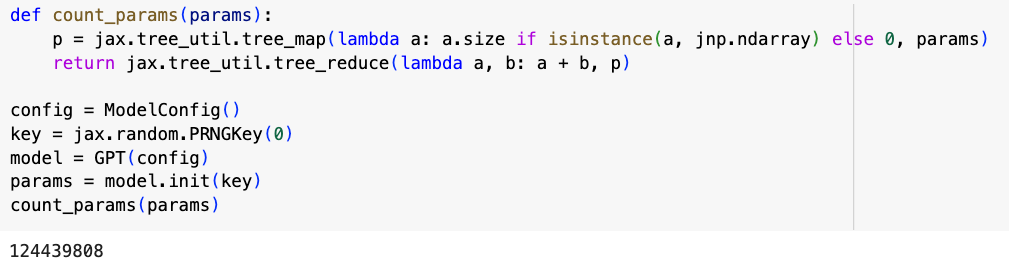

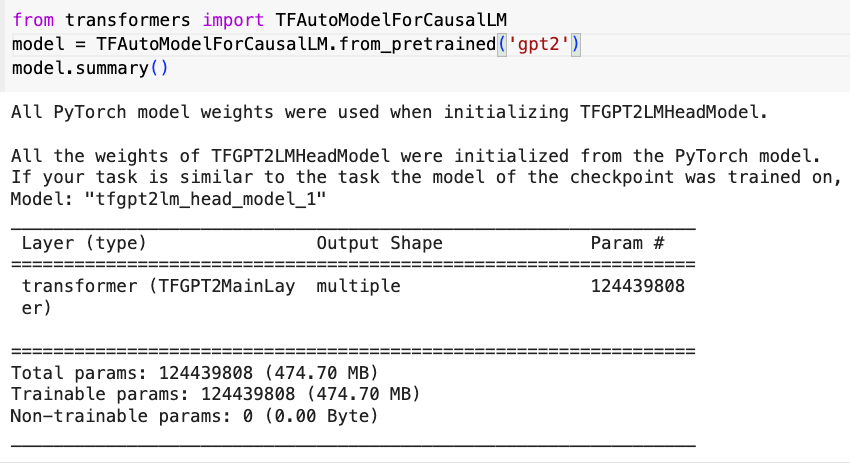

Now let’s varify the number of parameters: We first initialize the model config dataclass and the random key, then create a dummy inputs and feed in into the GPT model. Then we utilize the jax.util.treemap API to create a count parameter function. We got 124439808 (124M) parameters, same amount as Huggingface’s GPT2, BOOM!

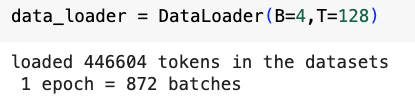

Let’s now overfit a small dataset. To make it comparable inAndrej’s video on Pytorch NanoGPT, let’s use the toy dataset that he shared in his video. We use the GPT2′ tokenizer from tiktoken library to tokenize all the texts from the input file, and convert the tokens into jax.numpy.array for Jax’s model training.

class DataLoader:

def __init__(self, B, T):

self.current_position = 0

self.B = B

self.T = T

with open("input.txt","r") as f:

text = f.read()

enc = tiktoken.get_encoding("gpt2")

self.tokens = jnp.array(enc.encode(text))

print(f"loaded {len(self.tokens)} tokens in the datasets" )

print(f" 1 epoch = {len(self.tokens)//(B*T)} batches")

def next_batch(self):

B,T = self.B, self.T

buf = self.tokens[self.current_position:self.current_position+B*T+1]

x,y = jnp.reshape(buf[:-1],(B,T)), jnp.reshape(buf[1:],(B,T))

self.current_position += B*T

if self.current_position + B*T+1 > len(self.tokens):

self.current_position = 0

return x,y

Next, let’s forget distributed training and optimization first, and just create a naive training loop for a sanity check. The first thing after intialize the model is to create a TrainState, a model state where we can update the parameters and gradients. The TrainState takes three important inputs: apply_fn (model forward function), params (model parameters from the init method), and tx (an Optax gradient transformation).

Then we use the train_step function to update the model state (gradients and parameters) to proceed the model training. Optax provide the softmax cross entropy as the loss function for the next token prediction task, and jax.value_and_grad calculates the gradients and the loss value for the loss function. Finally, we update the model’s state with the new parameters using the apply_gradients API. [ref] Don’t forget to jit the train_step function to reduce the computation overhead!

def init_train_state(key, config) -> TrainState:

model = GPT(config)

params = model.init(key)

optimizer = optax.adamw(3e-4, b1=0.9, b2=0.98, eps=1e-9, weight_decay=1e-1)

train_state = TrainState.create(

apply_fn=model.apply,

params=params,

tx=optimizer)

return train_state

@jax.jit

def train_step(state: TrainState, x: jnp.ndarray, y: jnp.ndarray) -> Tuple[jnp.ndarray, TrainState]:

def loss_fn(params: FrozenDict) -> jnp.ndarray:

logits = state.apply_fn(params, x, False)

loss = optax.softmax_cross_entropy_with_integer_labels(logits, y).mean()

return loss

loss, grads = jax.value_and_grad(loss_fn, has_aux=False)(state.params)

new_state = state.apply_gradients(grads=grads)

return loss, new_state

Now everything is ready for the poorman’s training loop.. Let’s check the loss value. The model’s prediction should be better than the random guess, so the loss should be lower than -ln(1/50257)≈10.825. What we expect from the overfitting a single batch is that: in the beginning the loss is close to 10.825, then it goes down to close to 0. Let’s take a batch of (x, y) and run the training loop for 50 times. I also add similar log to calculate the training speed.

As we can see, the loss value is exactly what we expect, and the training throughput is around 400–500 k token/sec. Which is already 40x faster than Pytorch’s initial version without any optimization in Andrej’s video. Note that we run the Jax scripts in 1 A100 GPU which should remove the hardware difference for the speed comparison. There is no .to(device) stuff to move your model or data from host CPU to device GPU, which is one of the benefits from Jax!

So that’s it and we made it. We will make the training 10x more faster in Part 2 with more optimizations…

Part 2: The journey of training optimization to 1350k tokens/sec in a single GPU!

“Unless otherwise noted, all images are by the author”

Let’s reproduce NanoGPT with JAX!(Part 1) was originally published in Towards Data Science on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Originally appeared here:

Let’s reproduce NanoGPT with JAX!(Part 1)

Go Here to Read this Fast! Let’s reproduce NanoGPT with JAX!(Part 1)

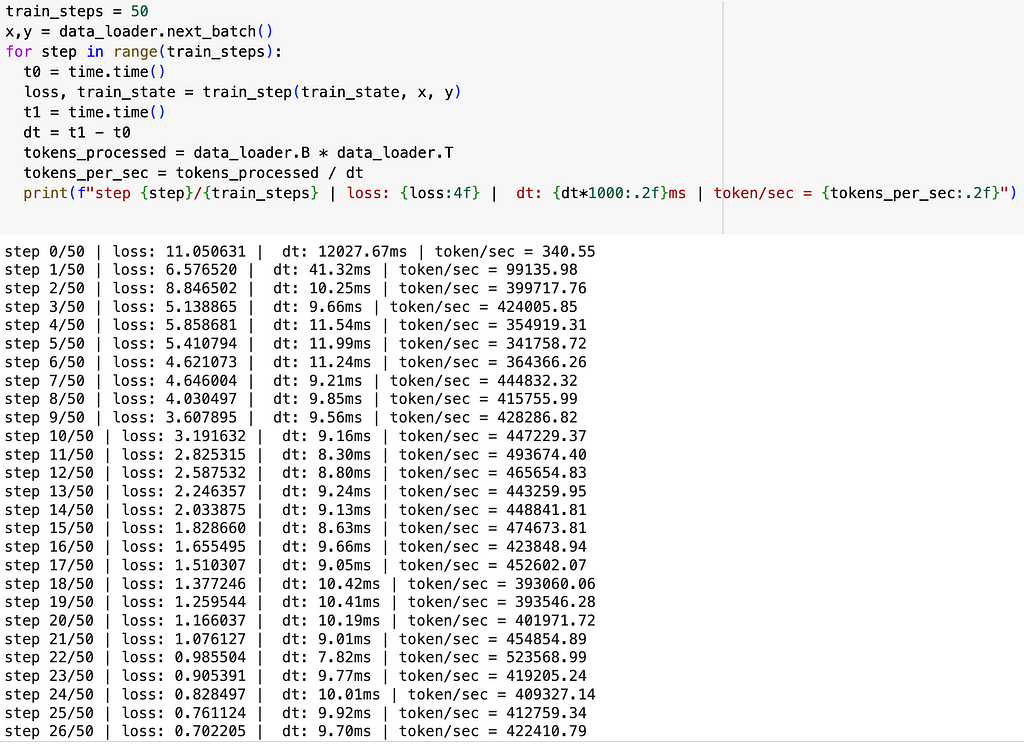

A data-based tribute to the International Owl Awareness Day

Originally appeared here:

The Secret Network of Owls

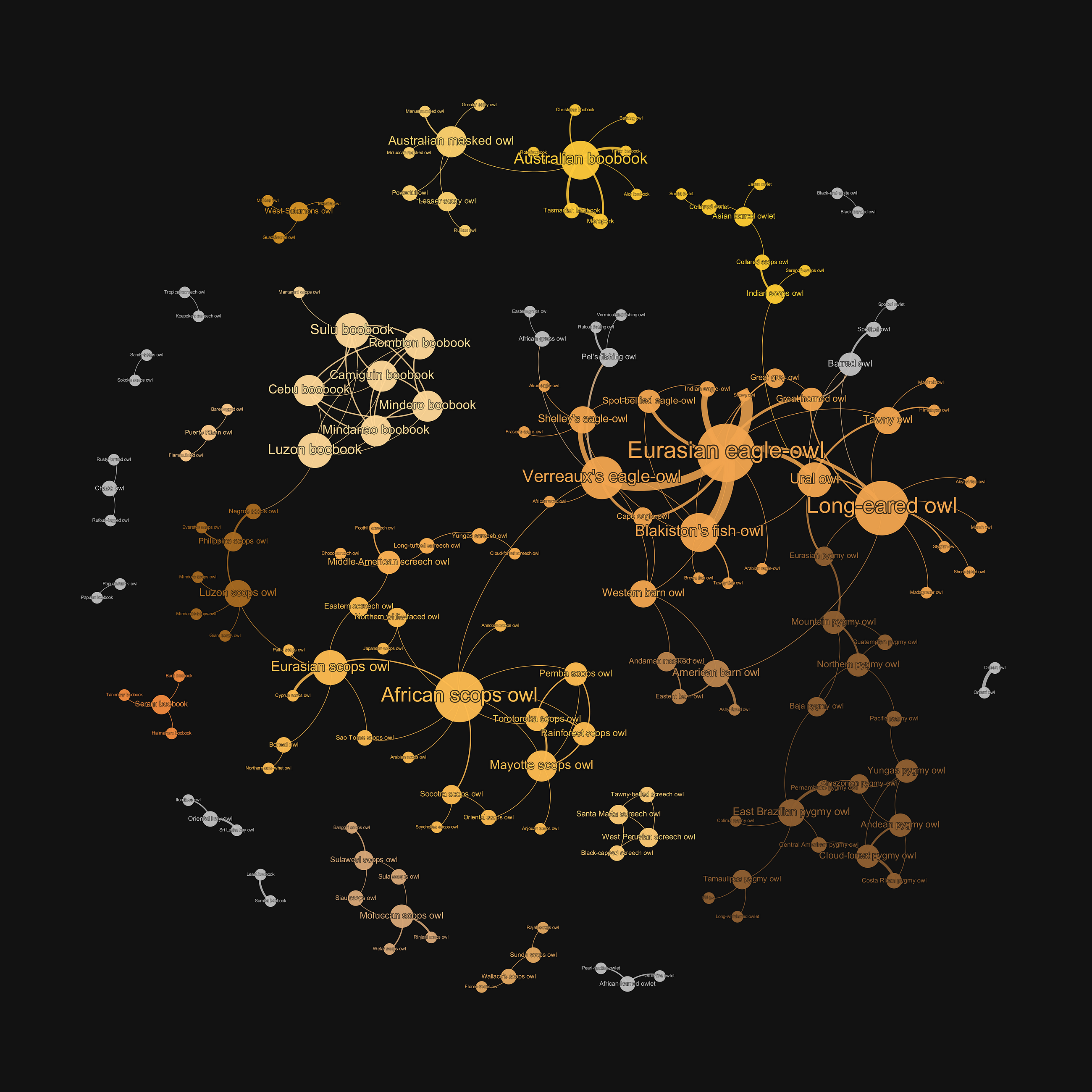

I have always had a soft spot for words that perfectly capture the essence of a concept. During one of my trips to Japan, I discovered the word Tsundoku. It refers to the habit of acquiring books and letting them pile up without reading them. I immediately fell in love with the word because, like many, I have a habit of buying more books than I can read. Some I eventually get to, while others simply accumulate.

There’s something amusing and oddly satisfying about these piles of unread books — they symbolise potential knowledge and the joy of collecting. They stand as a testament to our intellectual aspirations, even if we don’t always fulfil them.

As founder of Kindata.io and a consultant for large companies on data value, I often encounter usage of data catalogues that make me want to scream, “Tsundoku!”. These catalogues, like stacks of unread books, are filled with detailed descriptions of data that sits idle, giving a false sense of accomplishment. A book not read is knowledge wasted; similarly, data not exploited for business value is potential wasted.

Nobody likes waste, and the professionals I work with are no exception. They are eager to see their data used to its full potential. They also understand that getting there will require a change in mindset. Working in data, they also appreciate the power of well-named concepts. I have heard many terms being used for this work of alignment to business value, but I must say that I have become fond of one that is picking up: Data Value Lineage. This term resonates deeply with me because it perfectly captures what I am championing. It highlights the need to turn idle data into actionable insights by making sure that everything that you do in the data teams is firmly linked to value creation.

At first glance, choosing to name a concept one way instead of another might seem inconsequential. However, naming concepts is powerful especially if you need to bring with you an entire organisation.

In the sections that follow, we will delve deeper into the specifics of Data Value Lineage. After defining the concept and what it entails, we will explore how to get started with a pragmatic implementation approach within your data organisation.

Data value lineage is the aggregation of two terms commonly used among data professionals: data lineage and data value. Let’s get back to the roots of these concepts.

Data Lineage is defined by the IBM Knowledge Center:

“Data lineage is the process of tracking the flow of data over time, providing a clear understanding of where the data originated, how it has changed, and its ultimate destination within the data pipeline.”

“Data Value is the economic worth that an organisation can derive from its data. This includes both tangible benefits like revenue generation and cost savings, as well as intangible benefits like improved decision-making, enhanced customer experiences, and competitive advantage.”

This definition is synthesised from commonly accepted industry principles, as a direct authoritative source is not currently available.

The two previous definitions take us in different directions. Data lineage is all about understanding dependencies, bias, and potential quality issues. It provides explainability and helps data engineering teams repair broken pipelines. It is effectively a formal description of your data supply chains. Yet, for most people, it stops when the data is effectively used by an application.

Data value on the other hand focuses on something completely different: the contribution of data to the organisation business objectives. The underlying assumption is that this data value can be formally measured. We are firmly in the world of strategy, finance and business cases, not in the world of pipelines debugging.

I am now picturing Jean-Claude Van Damme performing one of his legendary splits on two high piles of unread books and thinking very hard about unifying these two concepts…

Here is the first formal definition of data value lineage.

“Data value lineage is the process of reconciling at all times the enterprise data assets (including their maintenance costs) and the main delivery tasks performed within a data organisation with the measured contribution to enterprise value drivers”

There we are, we have a formal definition! I would like to insist on a couple of aspects of this definition that I think are fundamental:

As you can see, data value lineage, while inherently a simple concept, covers a very wide scope. Inevitably, this involves bringing together individuals within your organisation with very different profiles, mandates and concerns. Let’s explore how to get things moving pragmatically in the right direction.

Getting to think and act across silos and mentalities is not trivial. Inertia is a powerful force and putting eyes blinders on is sometimes the only way to get anything done in large corporations.

Through the many change management projects that I have driven or even observed, I have found three invariably useful critical success factors:

The good news is that it is relatively easy to tick all three boxes with data value lineage.

What I have found particularly useful in rolling out a data value lineage approach across an organisation is to start with the three basic questions: what, how, why. This might sound simplistic but in reality most organisations are constantly mixing these three questions together and end up not getting any clear answers.

What refers to the data initiatives that are valued by the business. In the projects that we run, this covers both traditional analytics projects (dashboards, reports…) as well as data science / AI initiatives (predictive models, recommendation engines, chatbots…). The term that we use for a data-driven project that provides tangible business value is a business use case.

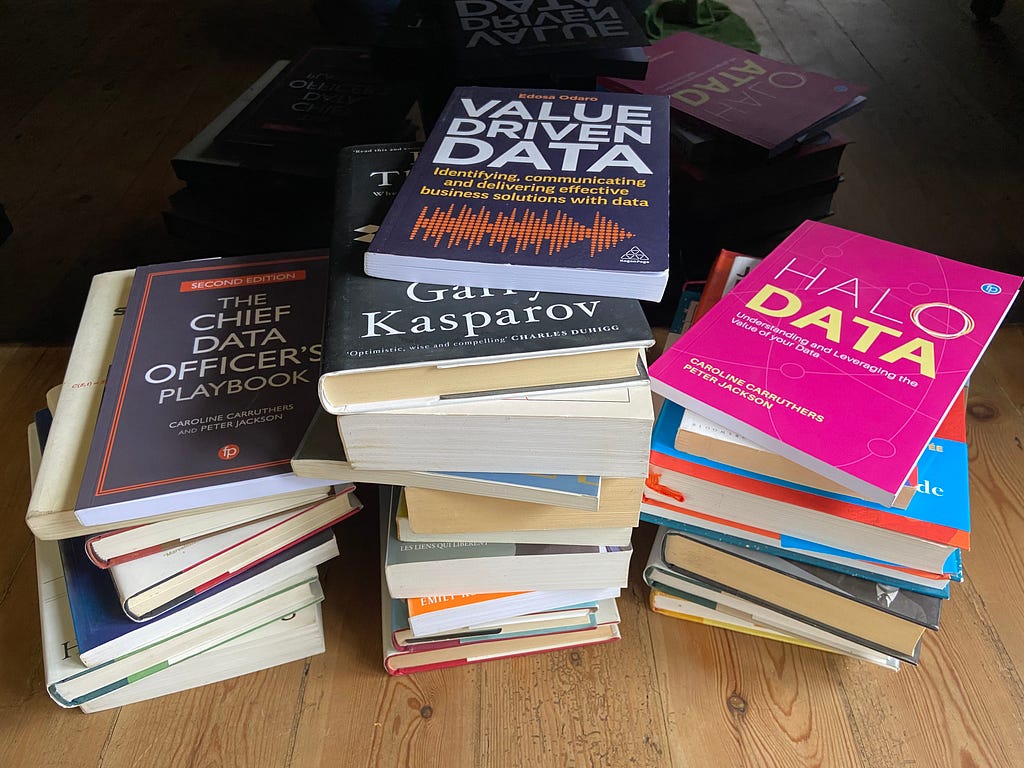

How covers many aspects but from the perspective of data value lineage, the most important one is data sourcing. More and more organisations, inspired by the principles of data mesh are adopting the concept of data product or productised data set. Contrary to business use cases, in this terminology, a data product does not contribute directly to business value, yet they come with maintenance costs.

Why is about the contribution to business value. How do you expect each business use case to contribute to one or several value drivers? Once the projects are delivered and enter into maintenance mode, is that contribution sustained?

Once we have a clear understanding of these three questions, we can start documenting the basic building blocks:

The first pragmatic level of data value lineage is to define the connections between these three levels.

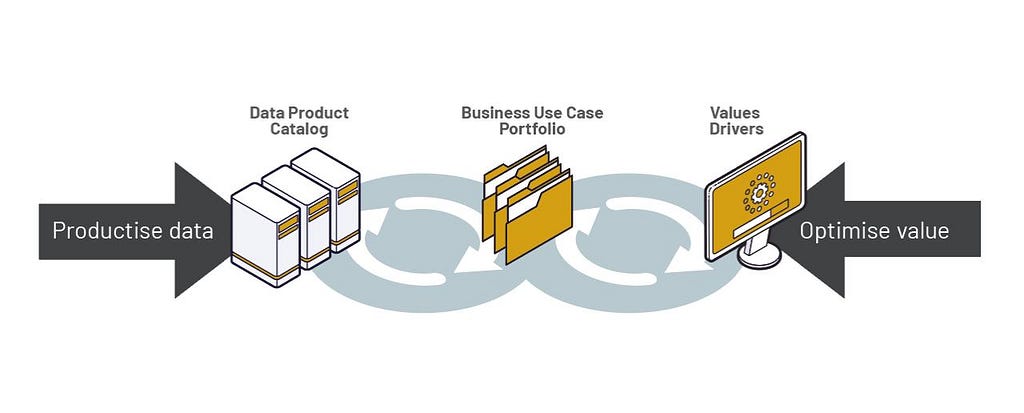

Let’s take a very simple example:

You want to optimise your energy consumption through a data-driven approach. The business use case (energy cost reduction) sources data from two data products (Company Energy Consumption and Utility Bills and Tariffs). It contributes to two business drivers: Cost Reduction and Sustainability.

The arrows between the data products, business use case and value drivers are the backbone of data value lineage. They make the link between the three fundamental questions. You will notice that the arrows are bi-directional:

Data value lineage is a powerful concept as it offers a structured approach to ensuring that every piece of data in your organisation contributes to business value. By reconciling data assets, tasks, and business outcomes, you can maximise the impact of your data initiatives.

It is also a great name that can rally people across the data, business and financial control organisations.

Don’t just find contentment in creating dozens of underused data products, fooling yourself with the illusion of value generation. Avoid the zen contemplation of unused piles of data, Tsundoku-style. Instead, take action and harness the full power of your data through data value lineage, ensuring that every effort directly contributes to business value generation.

Data Value Lineage, meaning at last? was originally published in Towards Data Science on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Originally appeared here:

Data Value Lineage, meaning at last?

Go Here to Read this Fast! Data Value Lineage, meaning at last?