Go Here to Read this Fast! DC Studios’ James Gunn explains why The Batman Part II was delayed

Originally appeared here:

DC Studios’ James Gunn explains why The Batman Part II was delayed

Go Here to Read this Fast! DC Studios’ James Gunn explains why The Batman Part II was delayed

Originally appeared here:

DC Studios’ James Gunn explains why The Batman Part II was delayed

Go Here to Read this Fast! Ken Jeong shares his emotional response to the Community movie script

Originally appeared here:

Ken Jeong shares his emotional response to the Community movie script

Go Here to Read this Fast! Samsung Galaxy S25 Ultra could miss out on a crucial tracking feature

Originally appeared here:

Samsung Galaxy S25 Ultra could miss out on a crucial tracking feature

NASA said on Friday that it received a signal from the Parker Solar Probe confirming that the spacecraft had survived its closest ever flyby of the sun. The approach took it just 3.8 million miles from the surface, passing within the sun’s corona and allowing for unprecedented data collection in the vicinity of a star. A few million miles might seem like a pretty great distance, but to put things in perspective, NASA explains, “If the solar system was scaled down with the distance between the sun and Earth the length of a football field, Parker Solar Probe would be just four yards from the end zone.”

The probe’s current orbit takes it closest to the sun about every three months. It’ll swing back around for two more close flybys in 2025, on March 22 and June 19. The probe is expected to transmit the data from its latest close approach soon, once it’s in a better location to do so. “The data that will come down from the spacecraft will be fresh information about a place that we, as humanity, have never been,” said Joe Westlake, the director of the Heliophysics Division at NASA Headquarters. “It’s an amazing accomplishment.”

This article originally appeared on Engadget at https://www.engadget.com/science/space/parker-solar-probe-survived-its-close-approach-to-the-sun-and-will-make-two-more-in-2025-180350510.html?src=rss

Originally appeared here:

Parker Solar Probe survived its close approach to the sun and will make two more in 2025

Python provides three main approaches to handle multiple tasks simultaneously: multithreading, multiprocessing, and asyncio.

Choosing the right model is crucial for maximising your program’s performance and efficiently using system resources. (P.S. It is also a common interview question!)

Without concurrency, a program processes only one task at a time. During operations like file loading, network requests, or user input, it stays idle, wasting valuable CPU cycles. Concurrency solves this by enabling multiple tasks to run efficiently.

But which model should you use? Let’s dive in!

Before jumping into Python’s concurrency models, let’s recap some foundational concepts.

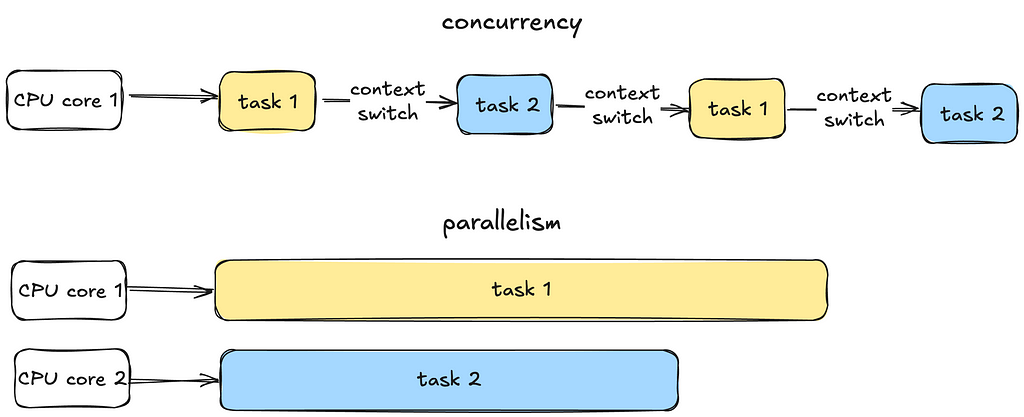

Concurrency is all about managing multiple tasks at the same time, not necessarily simultaneously. Tasks may take turns, creating the illusion of multitasking.

Parallelism is about running multiple tasks simultaneously, typically by leveraging multiple CPU cores.

Now let’s move on to some fundamental OS concepts — programs, processes and threads.

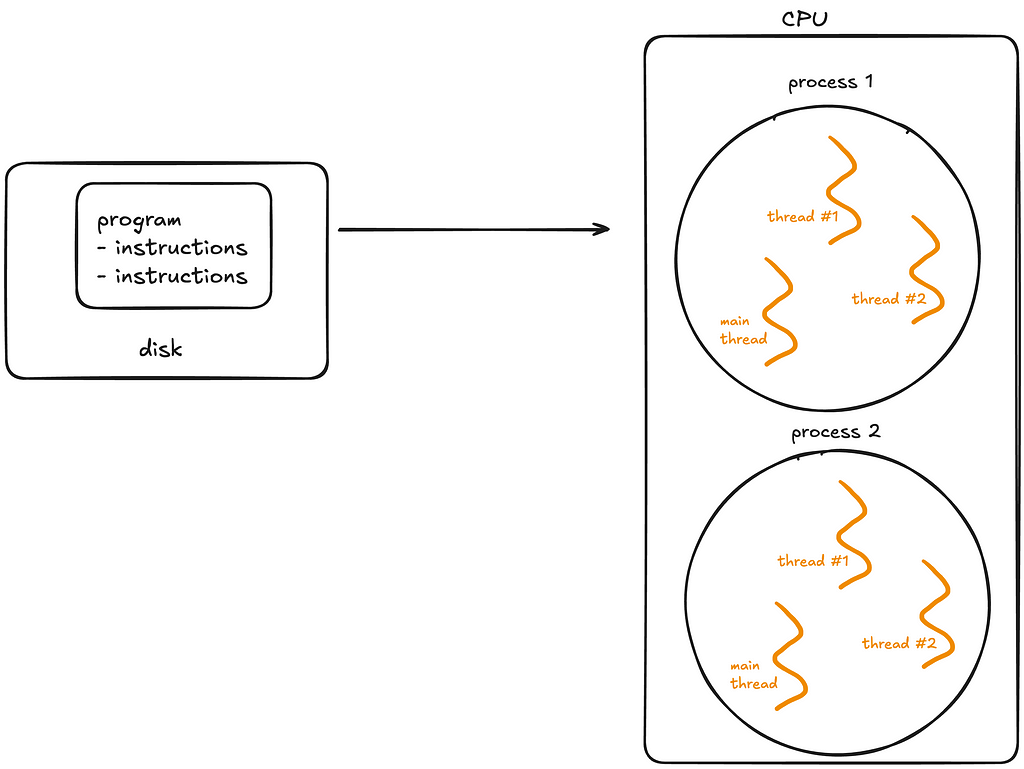

A program is simply a static file, like a Python script or an executable.

A program sits on disk, and is passive until the operating system (OS) loads it into memory to run. Once this happens, the program becomes a process.

A process is an independent instance of a running program.

A process has its own memory space, resources, and execution state. Processes are isolated from each other, meaning one process cannot interfere with another unless explicitly designed to do so via mechanisms like inter-process communication (IPC).

Processes can generally be categorised into two types:

Lifecycle of a process:

A thread is the smallest unit of execution within a process.

A process acts as a “container” for threads, and multiple threads can be created and destroyed over the process’s lifetime.

Every process has at least one thread — the main thread — but it can also create additional threads.

Threads share memory and resources within the same process, enabling efficient communication. However, this sharing can lead to synchronisation issues like race conditions or deadlocks if not managed carefully. Unlike processes, multiple threads in a single process are not isolated — one misbehaving thread can crash the entire process.

The CPU can execute only one task per core at a time. To handle multiple tasks, the operating system uses preemptive context switching.

During a context switch, the OS pauses the current task, saves its state and loads the state of the next task to be executed.

This rapid switching creates the illusion of simultaneous execution on a single CPU core.

For processes, context switching is more resource-intensive because the OS must save and load separate memory spaces. For threads, switching is faster because threads share the same memory within a process. However, frequent switching introduces overhead, which can slow down performance.

True parallel execution of processes can only occur if there are multiple CPU cores available. Each core handles a separate process simultaneously.

Let’s now explore Python’s specific concurrency models.

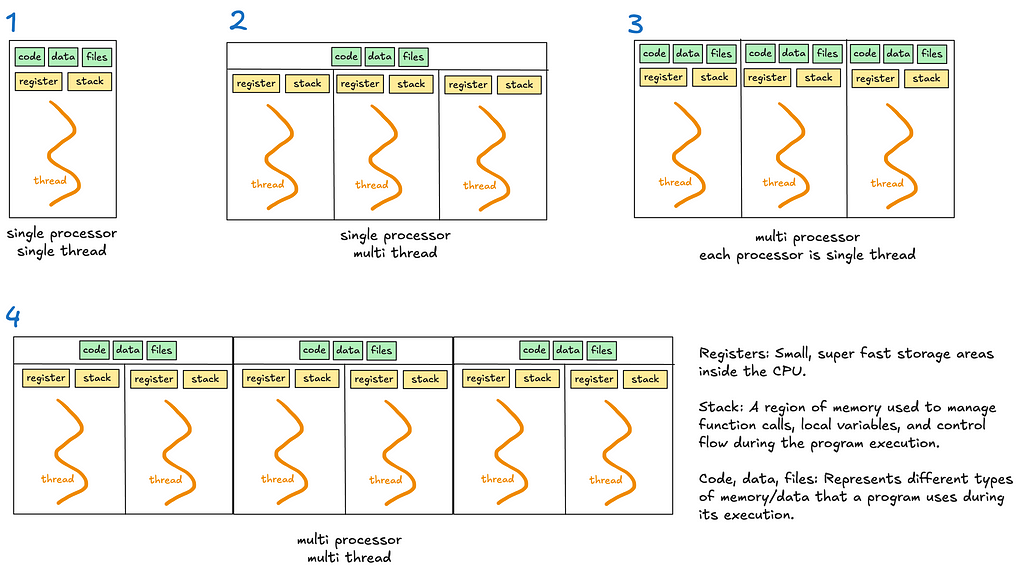

Multithreading allows a process to execute multiple threads concurrently, with threads sharing the same memory and resources (see diagrams 2 and 4).

However, Python’s Global Interpreter Lock (GIL) limits multithreading’s effectiveness for CPU-bound tasks.

The GIL is a lock that allows only one thread to hold control of the Python interpreter at any time, meaning only one thread can execute Python bytecode at once.

The GIL was introduced to simplify memory management in Python as many internal operations, such as object creation, are not thread safe by default. Without a GIL, multiple threads trying to access the shared resources will require complex locks or synchronisation mechanisms to prevent race conditions and data corruption.

When is GIL a bottleneck?

An interesting case worth noting is the use of time.sleep, which Python effectively treats as an I/O operation. The time.sleep function is not CPU-bound because it does not involve active computation or the execution of Python bytecode during the sleep period. Instead, the responsibility of tracking the elapsed time is delegated to the OS. During this time, the thread releases the GIL, allowing other threads to run and utilise the interpreter.

Multiprocessing enables a system to run multiple processes in parallel, each with its own memory, GIL and resources. Within each process, there may be one or more threads (see diagrams 3 and 4).

Multiprocessing bypasses the limitations of the GIL. This makes it suitable for CPU bound tasks that require heavy computation.

However, multiprocessing is more resource intensive due to separate memory and process overheads.

Unlike threads or processes, asyncio uses a single thread to handle multiple tasks.

When writing asynchronous code with the asyncio library, you’ll use the async/await keywords to manage tasks.

Asyncio runs an event loop that schedules tasks. Tasks voluntarily “pause” themselves when waiting for something, like a network response or a file read. While the task is paused, the event loop switches to another task, ensuring no time is wasted waiting.

This makes asyncio ideal for scenarios involving many small tasks that spend a lot of time waiting, such as handling thousands of web requests or managing database queries. Since everything runs on a single thread, asyncio avoids the overhead and complexity of thread switching.

The key difference between asyncio and multithreading lies in how they handle waiting tasks.

method 1: await coroutine

When you directly await a coroutine, the execution of the current coroutine pauses at the await statement until the awaited coroutine finishes. Tasks are executed sequentially within the current coroutine.

Use this approach when you need the result of the coroutine immediately to proceed with the next steps.

Although this might sound like synchronous code, it’s not. In synchronous code, the entire program would block during a pause.

With asyncio, only the current coroutine pauses, while the rest of the program can continue running. This makes asyncio non-blocking at the program level.

Example:

The event loop pauses the current coroutine until fetch_data is complete.

async def fetch_data():

print("Fetching data...")

await asyncio.sleep(1) # Simulate a network call

print("Data fetched")

return "data"

async def main():

result = await fetch_data() # Current coroutine pauses here

print(f"Result: {result}")

asyncio.run(main())

method 2: asyncio.create_task(coroutine)

The coroutine is scheduled to run concurrently in the background. Unlike await, the current coroutine continues executing immediately without waiting for the scheduled task to finish.

The scheduled coroutine starts running as soon as the event loop finds an opportunity, without needing to wait for an explicit await.

No new threads are created; instead, the coroutine runs within the same thread as the event loop, which manages when each task gets execution time.

This approach enables concurrency within the program, allowing multiple tasks to overlap their execution efficiently. You will later need to await the task to get it’s result and ensure it’s done.

Use this approach when you want to run tasks concurrently and don’t need the results immediately.

Example:

When the line asyncio.create_task() is reached, the coroutine fetch_data() is scheduled to start running immediately when the event loop is available. This can happen even before you explicitly await the task. In contrast, in the first await method, the coroutine only starts executing when the await statement is reached.

Overall, this makes the program more efficient by overlapping the execution of multiple tasks.

async def fetch_data():

# Simulate a network call

await asyncio.sleep(1)

return "data"

async def main():

# Schedule fetch_data

task = asyncio.create_task(fetch_data())

# Simulate doing other work

await asyncio.sleep(5)

# Now, await task to get the result

result = await task

print(result)

asyncio.run(main())

import asyncio

import time

def sync_task():

time.sleep(2)

return "Completed"

async def main():

result = await asyncio.to_thread(sync_task)

print(result)

asyncio.run(main())

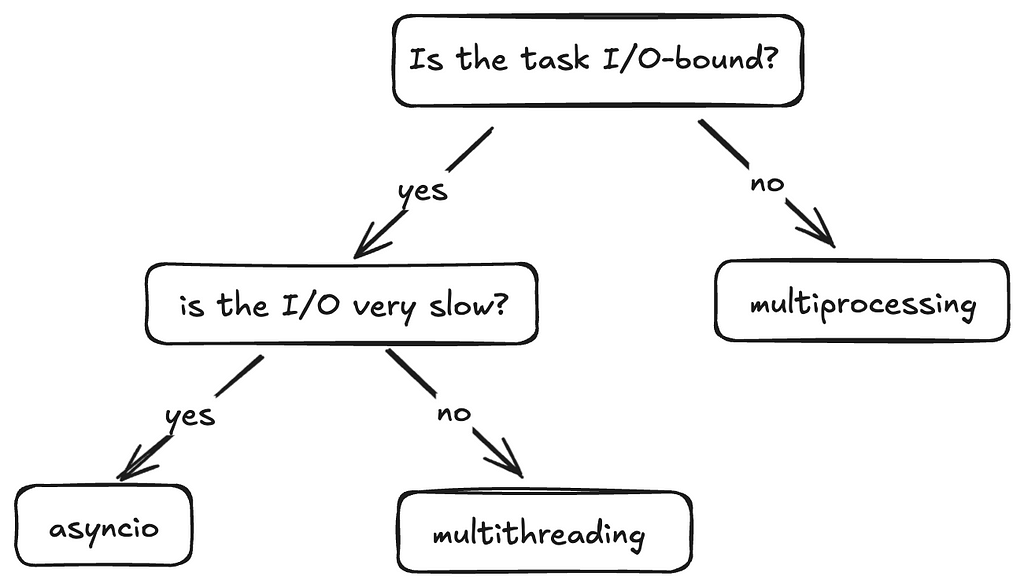

This flow is a good way to decide when to use what.

That’s it folks. There’s a lot more that this topic has to cover but I hope I’ve introduced to you the various concepts, and when to use each method.

Thanks for reading! I write regularly on Python, software development and the projects I build, so give me a follow to not miss out. See you in the next article 🙂

Deep Dive into Multithreading, Multiprocessing, and Asyncio was originally published in Towards Data Science on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Originally appeared here:

Deep Dive into Multithreading, Multiprocessing, and Asyncio

Go Here to Read this Fast! Deep Dive into Multithreading, Multiprocessing, and Asyncio

At this point, I’m pretty sure I’ve earned my reputation as the most tech-critical member of the AppleInsider staff through countless other pieces I’ve written. I’m sure that’ll also be reflected here.

When Mike asked me to write a piece about my setup, I scoffed. Surely, my setup would be far less impressive than my coworkers’ — and I still stand by that.

I owned the very first Retina iPad mini way back in 2014, but it was only ever a Netflix machine for me. With the release of the new seventh-generation model that’s all changed, and it might just be the defacto iPad from here on out.

The new 2024 iPad mini is the smallest tablet in a lineup dominated by superfast, super-big tablets. But after spending a few weeks with the new A17 Pro-powered, I think I finally get why you should buy one.

Go Here to Read this Fast! iPad mini 7 two-month review: Now I get it

Originally appeared here:

iPad mini 7 two-month review: Now I get it

Go Here to Read this Fast! Macs need Face ID, but not if it’s like Windows Hello

Originally appeared here:

Macs need Face ID, but not if it’s like Windows Hello