A way to program and tune prompt-agnostic LLM agent pipelines

I hate prompt engineering. For one thing, I do not want to prostrate before a LLM (“you are the world’s best copywriter … “), bribe it (“I will tip you $10 if you …”), or nag it (“Make sure to …”). For another, prompts are brittle — small changes to prompts can cause major changes to the output. This makes it hard to develop repeatable functionality using LLMs.

Unfortunately, developing LLM-based applications today involves tuning and tweaking prompts. Moving from writing code in a programming language that the computer follows precisely to writing ambiguous natural language instructions that are imperfectly followed does not seem like progress. That’s why I found working with LLMs a frustrating exercise — I prefer writing and debugging computer programs that I can actually reason about.

What if, though, you can program on top of LLMs using a high-level programming framework, and let the framework write and tune prompts for you? Would be great, wouldn’t it? This — the ability to build agent pipelines programmatically without dealing with prompts and to tune these pipelines in a data-driven and LLM-agnostic way — is the key premise behind DSPy.

An AI Assistant

To illustrate how DSPy works, I’ll build an AI assistant.

What’s an AI assistant? It’s a computer program that provides assistance to a human doing a task. The ideal AI assistant works proactively on behalf of the user (a chatbot can be a failsafe for functionality that is not easy to find in your product or a way end-users can reach out for customer support, but should not be the main/only AI assistance in your application). So, designing an AI assistant consists of thinking through a workflow and determining how you could want to streamline it using AI.

A typical AI assistant streamlines a workflow by (1) retrieving information such as company policies relevant to the task, (2) extracting information from documents such as those sent in by customers, (3) filling out forms or checklists based on textual analysis of the policies and documents, (4) collecting parameters and making function calls on the human’s behalf, and (5) identifying potential errors and highlighting risks.

The use case I will use to illustrate an AI assistant involves the card game bridge. Even though I’m building an AI assistant for bridge bidding, you don’t need to understand bridge to understand the concepts here. The reason I chose bridge is that there is a lot of jargon, quite a bit of human judgement involved, and several external tools that an advisor can use. These are the key characteristics of the industry problems and backoffice processes that you might want to build AI assistants for. But because it’s a game, there is no confidential information involved.

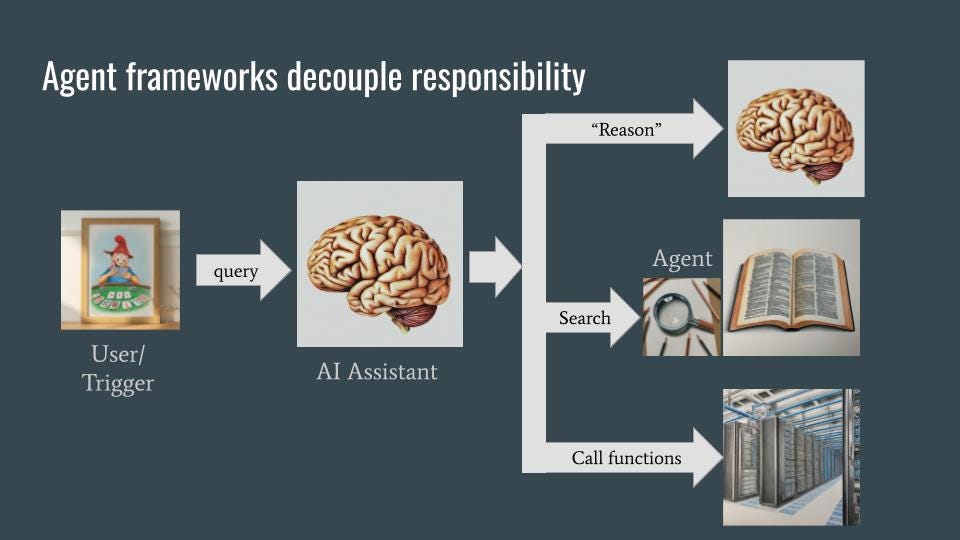

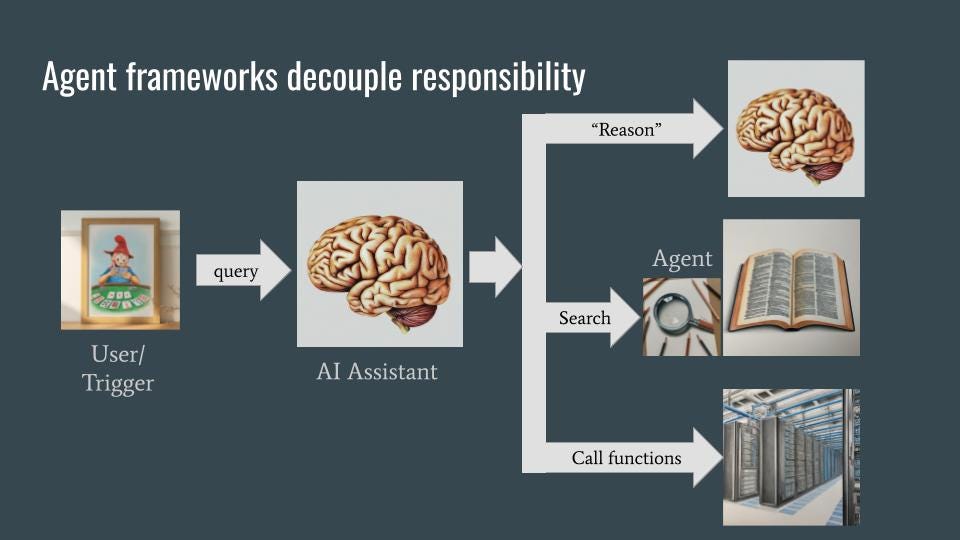

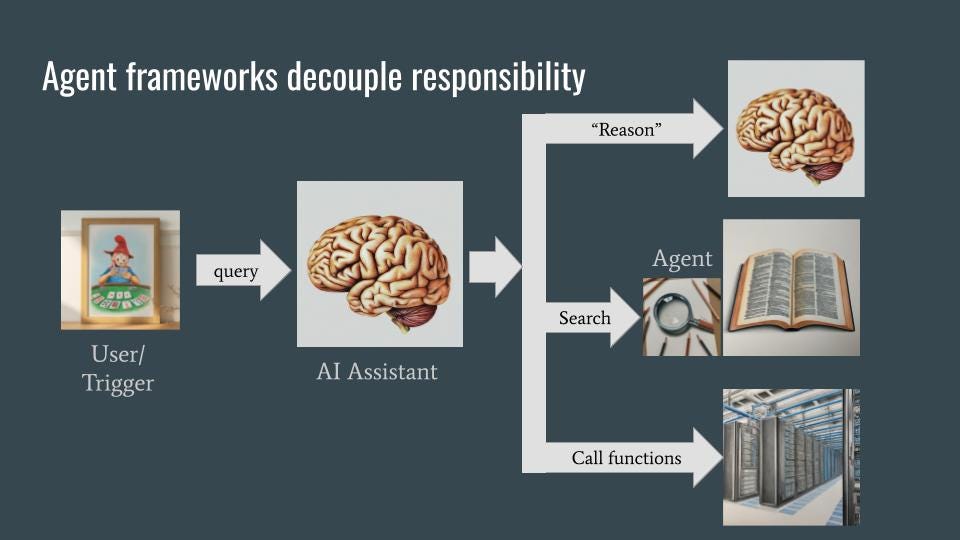

Agent Framework

The assistant, when asked a question like “What is Stayman?”, uses a number of backend services to carry out its task. These backend services are invoked via agents, which are themselves built using language models. As with microservices in software engineering, the use of agents and backend services allows for decoupling and specialization — the AI assistant does not need to know how things are done, only what it needs done and each agent can know how to do only its own thing.

In an agent framework, the agents can often be smaller language models (LMs) that need to be accurate, but don’t have world knowledge. The agents will be able to “reason” (through chain-of-thought), search (through Retrieval-Augmented-Generation), and do non-textual work (by extracting the parameters to pass into a backend function). Instead of having disparate capabilities or skills, the entire agent framework is fronted by an AI assistant that is an extremely fluent and coherent LLM. This LLM will know the intents it needs to handle and how to route those intents. It needs to have world knowledge as well. Often, there is a separate policy or guardrails LLM that acts as a filter. The AI assistant is invoked when the user makes a query (the chatbot use case) or when there is a triggering event (the proactive assistant use case).

Zero Shot prompting with DSPy

To build the whole architecture above, I’ll use DSPy. The entire code is on GitHub; start with bidding_advisor.py in that directory and follow along.

In DSPy, the process of sending a prompt to an LLM and getting a response back looks like this:

class ZeroShot(dspy.Module):

"""

Provide answer to question

"""

def __init__(self):

super().__init__()

self.prog = dspy.Predict("question -> answer")

def forward(self, question):

return self.prog(question="In the game of bridge, " + question)

There are four things happening in the snippet above:

- Write a subclass of dspy.Module

- In the init method, set up a LM module. The simplest is dspy.Predict which is a single call.

- The Predict constructor takes a signature. Here, I say that there is one input (question) and one output (answer).

- Write a forward() method that takes the input(s) specified (here: question) and returns the what was promised in the signature (here: answer). It does this by calling the dspy.Predict object created in the init method.

I could have just passed the question along as-is, but just to show you that I can somewhat affect the prompt, I added a bit of context.

Note that the code above is completely LLM-agnostic, and there is no groveling, bribery, etc. in the prompt.

To call the above module, you first initialize dspy with an LLM:

gemini = dspy.Google("models/gemini-1.0-pro",

api_key=api_key,

temperature=temperature)

dspy.settings.configure(lm=gemini, max_tokens=1024)

Then, you invoke your module:

module = ZeroShot()

response = module("What is Stayman?")

print(response)

When I did that, I got:

Prediction(

answer='Question: In the game of bridge, What is Stayman?nAnswer: A conventional bid of 2♣ by responder after a 1NT opening bid, asking opener to bid a four-card major suit if he has one, or to pass if he does not.'

)

Want to use a different LLM? Change the settings configuration lines to:

gpt35 = dspy.OpenAI(model="gpt-3.5-turbo",

api_key=api_key,

temperature=temperature)

dspy.settings.configure(lm=gpt35, max_tokens=1024)

Text Extraction

If all DSPy were doing was making it easier to call out to LLMs and abstract out the LLM, people wouldn’t be this excited about DSPy. Let’s continue to build out the AI assistant and tour some of the other advantages as we go along.

Let’s say that we want to use an LLM to do some entity extraction. We can do this by instructing the LLM to identify the thing we want to extract (date, product SKU, etc.). Here, we’ll ask it to find bridge jargon:

class Terms(dspy.Signature):

"""

List of extracted entities

"""

prompt = dspy.InputField()

terms = dspy.OutputField(format=list)

class FindTerms(dspy.Module):

"""

Extract bridge terms from a question

"""

def __init__(self):

super().__init__()

self.entity_extractor = dspy.Predict(Terms)

def forward(self, question):

max_num_terms = max(1, len(question.split())//4)

instruction = f"Identify up to {max_num_terms} terms in the following question that are jargon in the card game bridge."

prediction = self.entity_extractor(

prompt=f"{instruction}n{question}"

)

return prediction.terms

While we could have represented the signature of the module as “prompt -> terms”, we can also represent the signature as a Python class.

Calling this module on a statement:

module = FindTerms()

response = module("Playing Stayman and Transfers, what do you bid with 5-4 in the majors?")

print(response)

We’ll get:

['Stayman', 'Transfers']

Note how concise and readable this is.

RAG

DSPy comes built-in with several retrievers. But these essentially just functions and you can wrap existing retrieval code into a dspy.Retriever. It supports several of the more popular ones, including ChromaDB:

from chromadb.utils import embedding_functions

default_ef = embedding_functions.DefaultEmbeddingFunction()

bidding_rag = ChromadbRM(CHROMA_COLLECTION_NAME, CHROMADB_DIR, default_ef, k=3)

Of course, I had to get a document on bridge bidding, chunk it, and load it into ChromaDB. That code is in the repo if you are interested, but I’ll omit it as it’s not relevant to this article.

Orchestration

So now you have all the agents implemented, each as its own dspy.Module. Now, to build the orchestrator LLM, the one that receives the command or trigger and invokes the agent modules in some fashion.

Orchestration of the modules also happens in a dspy.Module:

class AdvisorSignature(dspy.Signature):

definitions = dspy.InputField(format=str) # function to call on input to make it a string

bidding_system = dspy.InputField(format=str) # function to call on input to make it a string

question = dspy.InputField()

answer = dspy.OutputField()

class BridgeBiddingAdvisor(dspy.Module):

"""

Functions as the orchestrator. All questions are sent to this module.

"""

def __init__(self):

super().__init__()

self.find_terms = FindTerms()

self.definitions = Definitions()

self.prog = dspy.ChainOfThought(AdvisorSignature, n=3)

def forward(self, question):

terms = self.find_terms(question)

definitions = [self.definitions(term) for term in terms]

bidding_system = bidding_rag(question)

prediction = self.prog(definitions=definitions,

bidding_system=bidding_system,

question="In the game of bridge, " + question,

max_tokens=-1024)

return prediction.answer

Instead of using dspy.Predict for the final step, I’ve used a ChainOfThought (COT=3).

Optimizer

Now that we have the entire chain all set up, we can of course, simply call the orchestrator module to test it out. But more important, we can have dspy automatically tune the prompts for us based on example data.

To load in these examples and ask dspy to tune it (this is called a teleprompter, but the name will be changed to Optimizer, a much more descriptive name for what it does), I do:

traindata = json.load(open("trainingdata.json", "r"))['examples']

trainset = [dspy.Example(question=e['question'], answer=e['answer']) for e in traindata]

# train

teleprompter = teleprompt.LabeledFewShot()

optimized_advisor = teleprompter.compile(student=BridgeBiddingAdvisor(), trainset=trainset)

# use optimized advisor just like the original orchestrator

response = optimized_advisor("What is Stayman?")

print(response)

I used just 3 examples in the example above, but obviously, you’d use hundreds or thousands of examples to get a properly tuned set of prompts. Worth noting is that the tuning is done over the entire pipeline; you don’t have to mess around with the modules one by one.

Is the optimized pipeline better?

While the original pipeline returned the following for this question (intermediate outputs are also shown, and Two spades is wrong):

a: Playing Stayman and Transfers, what do you bid with 5-4 in the majors?

b: ['Stayman', 'Transfers']

c: ['Stayman convention | Stayman is a bidding convention in the card game contract bridge. It is used by a partnership to find a 4-4 or 5-3 trump fit in a major suit after making a one notrump (1NT) opening bid and it has been adapted for use after a 2NT opening, a 1NT overcall, and many other natural notrump bids.', "Jacoby transfer | The Jacoby transfer, or simply transfers, in the card game contract bridge, is a convention initiated by responder following partner's notrump opening bid that forces opener to rebid in the suit ranked just above that bid by responder. For example, a response in diamonds forces a rebid in hearts and a response in hearts forces a rebid in spades. Transfers are used to show a weak hand with a long major suit, and to ensure that opener declare the hand if the final contract is in the suit transferred to, preventing the opponents from seeing the cards of the stronger hand."]

d: ['stayman ( possibly a weak ... 1602', '( scrambling for a two - ... 1601', '( i ) two hearts is weak ... 1596']

Two spades.

The optimized pipeline returns the correct answer of “Smolen”:

a: Playing Stayman and Transfers, what do you bid with 5-4 in the majors?

b: ['Stayman', 'Transfers']

c: ['Stayman convention | Stayman is a bidding convention in the card game contract bridge. It is used by a partnership to find a 4-4 or 5-3 trump fit in a major suit after making a one notrump (1NT) opening bid and it has been adapted for use after a 2NT opening, a 1NT overcall, and many other natural notrump bids.', "Jacoby transfer | The Jacoby transfer, or simply transfers, in the card game contract bridge, is a convention initiated by responder following partner's notrump opening bid that forces opener to rebid in the suit ranked just above that bid by responder. For example, a response in diamonds forces a rebid in hearts and a response in hearts forces a rebid in spades. Transfers are used to show a weak hand with a long major suit, and to ensure that opener declare the hand if the final contract is in the suit transferred to, preventing the opponents from seeing the cards of the stronger hand."]

d: ['stayman ( possibly a weak ... 1602', '( scrambling for a two - ... 1601', '( i ) two hearts is weak ... 1596']

After a 1NT opening, Smolen allows responder to show 5-4 in the majors with game-forcing values.

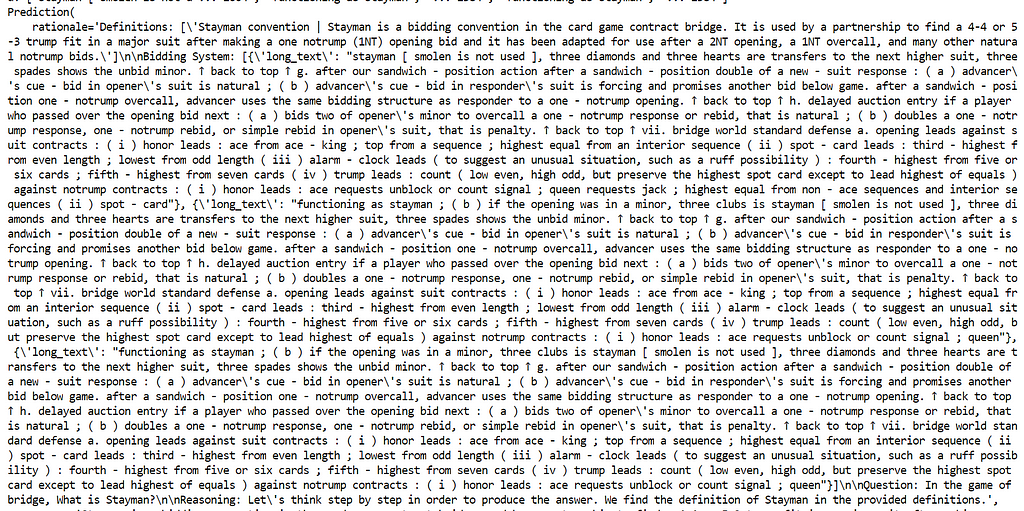

The reason is the prompt that dspy has created. For the question “What is Stayman?”, for example, note that it has built a rationale out of the term definitions, and several matches in the RAG:

Again, I didn’t write any of the tuned prompt above. It was all written for me. You can also see where this is headed in the future— you might be able to fine-tune the entire pipeline to run on a smaller LLM.

Enjoy!

Next steps

- Look at my code in GitHub, starting with bidding_advisor.py.

- Read more about DSPy here: https://dspy-docs.vercel.app/docs/intro

- Learn how to play bridge here: https://www.trickybridge.com/ (sorry, couldn’t resist).

Building an AI Assistant with DSPy was originally published in Towards Data Science on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Originally appeared here:

Building an AI Assistant with DSPy

Go Here to Read this Fast! Building an AI Assistant with DSPy