Should you have control over whether information about you gets used in training generative AI?

I’m sure lots of you reading this have heard about the recent controversy where LinkedIn apparently began silently using user personal data for training LLMs without notifying users or updating their privacy policy to allow for this. As I noted at the time over there, this struck me as a pretty startling move, given what we increasingly know about regulatory postures around AI and general public concern. In more recent news, online training platform Udemy has done something somewhat similar, where they quietly offered instructors a small window for opting out of having their personal data and course materials used in training AI, and have closed that window, allowing no more opting out. In both of these cases, businesses have chosen to use passive opt-in frameworks, which can have pros and cons.

To explain what happened in these cases, let’s start with some level setting. Social platforms like Udemy and LinkedIn have two general kinds of content related to users. There’s personal data, meaning information you provide (or which they make educated guesses about) that could be used alone or together to identify you in real life. Then, there’s other content you create or post, including things like comments or Likes you put on other people’s posts, slide decks you create for courses, and more. Some of that content is probably not qualified as personal data, because it would not have any possibility of identifying you individually. This doesn’t mean it isn’t important to you, however, but data privacy doesn’t usually cover those things. Legal protections in various jurisdictions, when they exist, usually cover personal data, so that’s what I’m going to focus on here.

The LinkedIn Story

LinkedIn has a general and very standard policy around the rights to general content (not personal data), where they get non-exclusive rights that permit them to make this content visible to users, generally making their platform possible.

However, a separate policy governs data privacy, as it relates to your personal data instead of the posts you make, and this is the one that’s been at issue in the AI training situation. Today (September 30, 2024), it says:

How we use your personal data will depend on which Services you use, how you use those Services and the choices you make in your settings. We may use your personal data to improve, develop, and provide products and Services, develop and train artificial intelligence (AI) models, develop, provide, and personalize our Services, and gain insights with the help of AI, automated systems, and inferences, so that our Services can be more relevant and useful to you and others. You can review LinkedIn’s Responsible AI principles here and learn more about our approach to generative AI here. Learn more about the inferences we may make, including as to your age and gender and how we use them.

Of course, it didn’t say this back when they started using your personal data for AI model training. The earlier version from mid-September 2024 (thanks to the Wayback Machine) was:

How we use your personal data will depend on which Services you use, how you use those Services and the choices you make in your settings. We use the data that we have about you to provide and personalize our Services, including with the help of automated systems and inferences we make, so that our Services (including ads) can be more relevant and useful to you and others.

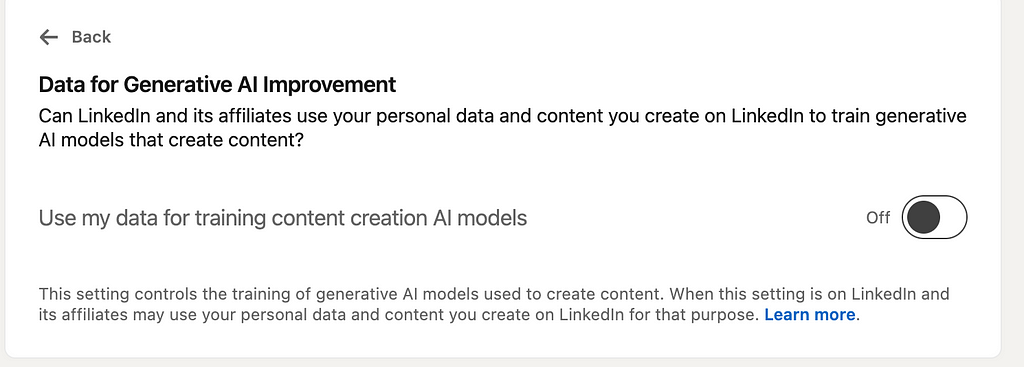

In theory, “with the help of automated systems and inferences we make” could be stretched in some ways to include AI, but that would be a tough sell to most users. However, before this text was changed on September 18, people had already noticed that a very deeply buried opt-out toggle had been added to the LinkedIn website that looks like this:

(My toggle is Off because I changed it, but the default is “On”.)

This suggests strongly that LinkedIn was already using people’s personal data and content for generative AI development before the terms of service were updated. We can’t tell for sure, of course, but lots of users have questions.

The Udemy Story

For Udemy’s case, the facts are slightly different (and new facts are being uncovered as we speak) but the underlying questions are similar. Udemy teachers and students provide large quantities of personal data as well as material they have written and created to the Udemy platform, and Udemy provides the infrastructure and coordination to allow courses to take place.

Udemy published an Instructor Generative AI policy in August, and this contains quite a bit of detail about the data rights they want to have, but it is very short on detail about what their AI program actually is. From reading the document, I’m very unclear as to what models they plan to train or are already training, or what outcomes they expect to achieve. It doesn’t distinguish between personal data, such as the likeness or personal details of instructors, and other things like lecture transcripts or comments. It seems clear that this policy covers personal data, and they’re pretty open about this in their privacy policy as well. Under “What We Use Your Data For”, we find:

Improve our Services and develop new products, services, and features (all data categories), including through the use of AI consistent with the Instructor GenAI Policy (Instructor Shared Content);

The “all data categories” they refer to include, among others:

- Account Data: username, password, but for instructors also “government ID information, verification photo, date of birth, race/ethnicity, and phone number” if you provide it

- Profile Data: “photo, headline, biography, language, website link, social media profiles, country, or other data.”

- System Data: “your IP address, device type, operating system type and version, unique device identifiers, browser, browser language, domain and other systems data, and platform types.”

- Approximate Geographic Data: “country, city, and geographic coordinates, calculated based on your IP address.”

But all of these categories can contain personal data, sometimes even PII, which is protected by comprehensive data privacy legislation in a number of jurisdictions around the world.

The generative AI move appears to have been rolled out quietly starting this summer, and like with LinkedIn, it’s an opt-out mechanism, so users who don’t want to participate must take active steps. They don’t seem to have started all this before changing their privacy policy, at least so far as we can tell, but in an unusual move, Udemy has chosen to make opt-out a time limited affair, and their instructors have to wait until a specified period each year to make changes to their involvement. This has already begun to make users feel blindsided, especially because the notifications of this time window were evidently not shared broadly. Udemy was not doing anything new or unexpected from an American data privacy perspective until they implemented this strange time limit on opt-out, provided they updated their privacy policy and made at least some attempt to inform users before they started training on the personal data.

(There’s also a question of the IP rights of teachers on the platform to their own creations, but that’s a question outside the scope of my article here, because IP law is very different from privacy law.)

Ethics

With these facts laid out, and inferring that LinkedIn was in fact starting to use people’s data for training GenAI models before notifying them, where does that leave us? If you’re a user of one of these platforms, does this matter? Should you care about any of this?

I’m going suggest there are a few important reasons to care about these developing patterns of data use, independent of whether you personally mind having your data included in training sets generally.

Your personal data creates risk.

Your personal data is valuable to these companies, but it also constitutes risk. When your data is out there being moved around and used for multiple purposes, including training AI, the risk of breach or data loss to bad actors is increased as more copies are made. In generative AI there is also a risk that poorly trained LLMs can accidentally release personal information directly in their output. Every new model that uses your data in training is an opportunity for unintended exposure of your data in these ways, especially because lots of people in machine learning are woefully unaware of the best practices for protecting data.

The principle of informed consent should be taken seriously.

Informed consent is a well known bedrock principle in biomedical research and healthcare, but it doesn’t get as much attention in other sectors. The idea is that every individual has rights that should not be abridged without that individual agreeing, with full possession of the pertinent facts so they can make their decision carefully. If we believe that protection of your personal data is part of this set of rights, then informed consent should be required for these kinds of situations. If we let companies slide when they ignore these rights, we are setting a precedent that says these violations are not a big deal, and more companies will continue behaving the same way.

Dark patterns can constitute coercion.

In social science, there is quite a bit of scholarship about opt-in and opt-out as frameworks. Often, making a sensitive issue like this opt-out is meant to make it hard for people to exercise their true choices, either because it’s difficult to navigate, or because they don’t even realize they have an option. Entities have the ability to encourage and even coerce behavior in the direction that benefits business by the way they structure the interface where people assert their choices. This kind of design with coercive tendencies falls into what we call dark patterns of user experience design online. When you add on the layer of Udemy limiting opt-out to a time window, this becomes even more problematic.

This is about images and multimedia as well as text.

This might not occur to everyone immediately, but I just want to highlight that when you upload a profile photo or any kind of personal photographs to these platforms, that becomes part of the data they collect about you. Even if you might not be so concerned with your comment on a LinkedIn post being tossed in to a model training process, you might care more that your face is being used to train the kinds of generative AI models that generate deepfakes. Maybe not! But just keep this in mind when you consider your data being used in generative AI.

What to do?

At this time, unfortunately, affected users have few choices when it comes to reacting to these kinds of unsavory business practices.

If you become aware that your data is being used for training generative AI and you’d prefer that not happen, you can opt out, if the business allows it. However, if (as in the case of Udemy) they limit that option, or don’t offer it at all, you have to look to the regulatory space. Many Americans are unlikely to have much recourse, but comprehensive data privacy laws like CCPA often touch on this sort of thing a bit. (See the IAPP tracker to check your state’s status.) CCPA generally permits opt-out frameworks, where a user taking no action is interpreted as consent. However, CCPA does require that opting out is not made outlandishly difficult. For example, you can’t require opt-outs be sent as a paper letter in the mail when you are able to give affirmative consent by email. Companies must also respond in 15 days to an opt-out request. Is Udemy limiting the opt-out to a specific timeframe once a year going to fit the bill?

But let’s step back. If you have no awareness that your data is being used to train AI, and you find out after the fact, what do you do then? Well, CCPA lets the consent be passive, but it does require that you be informed about the use of your personal data. Disclosure in a privacy policy is usually good enough, so given that LinkedIn didn’t do this at the outset, that might be cause for some legal challenges.

Notably, EU residents likely won’t have to worry about any of this, because the laws that protect them are much clearer and more consistent. I’ve written before about the EU AI Act, which has quite a bit of restriction on how AI can be applied, but it doesn’t really cover consent or how data can be used for training. Instead, GDPR is more likely to protect people from the kinds of things that are happening here. Under that law, EU residents must be informed and asked to positively affirm their consent, not just be given a chance to opt out. They must also have the ability to revoke consent for use of their personal data, and we don’t know if a time limited window for such action would pass muster, because the GDPR requirement is that a request to stop processing someone’s personal data must be handled within a month.

Lessons Learned

We don’t know with clarity what Udemy and LinkedIn are actually doing with this personal data, aside from the general idea that they’re training generative AI models, but one thing I think we can learn from these two news stories is that protecting individuals’ data rights can’t be abdicated to corporate interests without government engagement. For all the ethical businesses out there who are careful to notify customers and make opt-out easy, there are going to be many others that will skirt the rules and do the bare minimum or less unless people’s rights are protected with enforcement.

Read more of my work at www.stephaniekirmer.com.

Further Reading

https://www.datagrail.io/blog/data-privacy/opt-out-and-opt-in-consent-explained

- LinkedIn Is Training AI on User Data Before Updating Its Terms of Service

- US State Privacy Legislation Tracker

The privacy policies

https://web.archive.org/web/20240917144440/https://www.linkedin.com/legal/privacy-policy#use

https://www.linkedin.com/blog/member/trust-and-safety/updates-to-our-terms-of-service-2024

https://www.linkedin.com/legal/privacy-policy#use

https://www.udemy.com/terms/privacy/#section1

GDPR and CCPA

Consent in Training AI was originally published in Towards Data Science on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Originally appeared here:

Consent in Training AI