Emotions-in-the-Loop

Exploring the Legal Framework for Emotion in Emotion Recognition Tech

Recently I have started writing the series Emotions-in-the-Loop, where in the pilot (“Analyzing the Life of (Scanned) Jane”) I imagined an ultimate personal assistant interconnected with various personal devices and equipped with multiple emotion recognition systems. The reasons I wrote the first admittedly very sci-fi-like essay were:

- Having some fun before tangling myself into the legal nitty-gritty of analyzing the interconnected system.

- Raising at least some of the questions I wish to address in the series.

Still, before we can get into any of the two, I thought it was necessary to devote some attention to the question of what are emotions in this context. Both legally and technically speaking. And as we’ll soon see these two meanings are inextricably connected. Now, to not waste too much time and space here, let’s dive into it!

1. The Power of Emotions

“Emotion pulls the levers of our lives, whether it be by the song in our heart, or the curiosity that drives our scientific inquiry. Rehabilitation counselors, pastors, parents, and to some extent, politicians, know that it is not laws that exert the greatest influence on people, but the drumbeat to which they march.”

R.W. Picard

Emotions have always fascinated us. From when Aristotle described them as “those feeling that so change men as to affect their judgements.”[1] Over Charles Darwin and William James, who first connected emotions with their bodily manifestations and causes.[2] All the way to technologies, such as those used by our lovely, scanned Jane, that collect and interpret those bodily manifestations and appear to know us better than we know ourselves as a consequence.

This fascination has driven us towards discovering not just the power of emotions, but also ways as to how one can influence them. And that both to make ourselves and others feel better, as well as to deceive and manipulate. Now enter artificial intelligence, which graciously provided the possibility to both recognize and influence emotions at scale. However, despite how deeply fascinated we appear to be with emotions and the power they wield over us, our laws still fall short of protecting us from malevolent emotional manipulation. One of the reasons why this might be the case is because we are still not really sure what emotions are in general, let alone legally speaking. So let’s try and see if we can at least answer the second question, even if the answer to the first continues to elude us.

2. Emotions as (Personal) Data?

One thing that may come to mind when thinking about emotions legally, and especially in the context of artificial intelligence, is that they are some kind of data. Maybe even personal data. After all, what can be more personal than emotions? Than your feelings that you so carefully keep to yourself? Well, let’s briefly consider this hypothesis.

Personal data under the GDPR is defined as “any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person.” An identifiable natural person being the one who can (at least theoretically) be identified by someone somewhere, regardless of whether directly or indirectly. The slightly problematic thing about emotions in this context is that they are universal. Sadness, happiness, anger, or excitement don’t tell me anything that would make me identify the subject experiencing these emotions. But this is an overly simplistic approach.

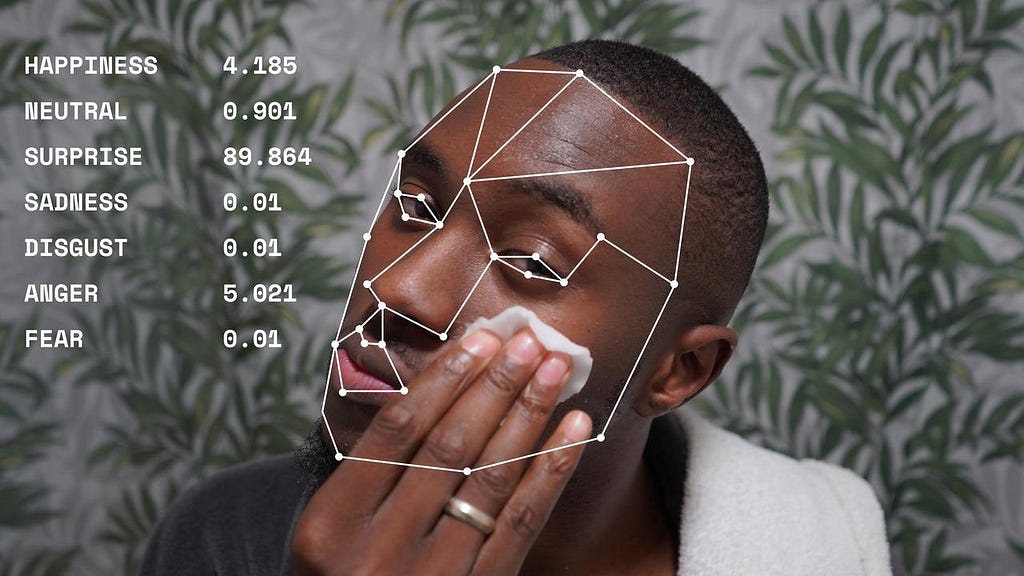

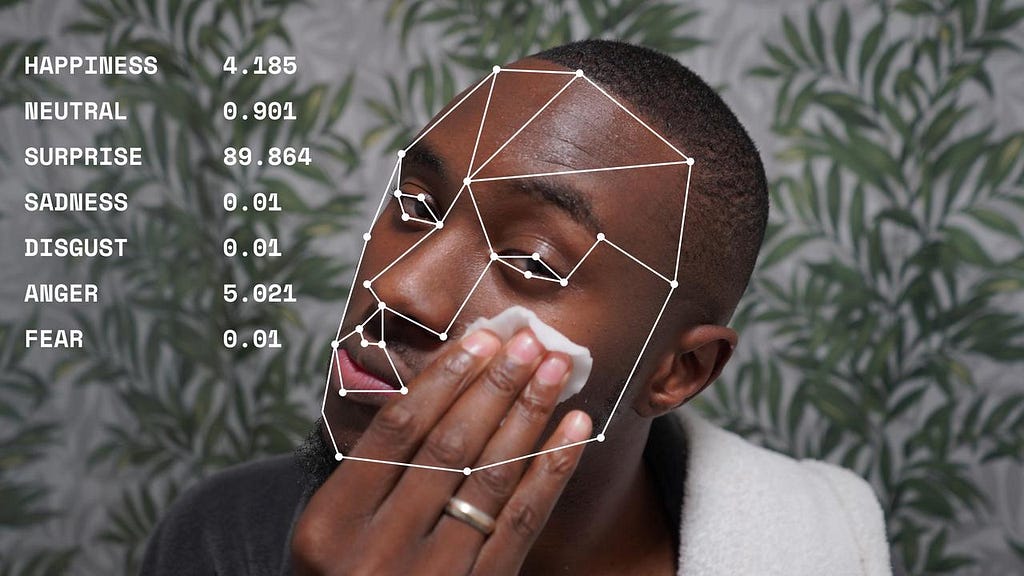

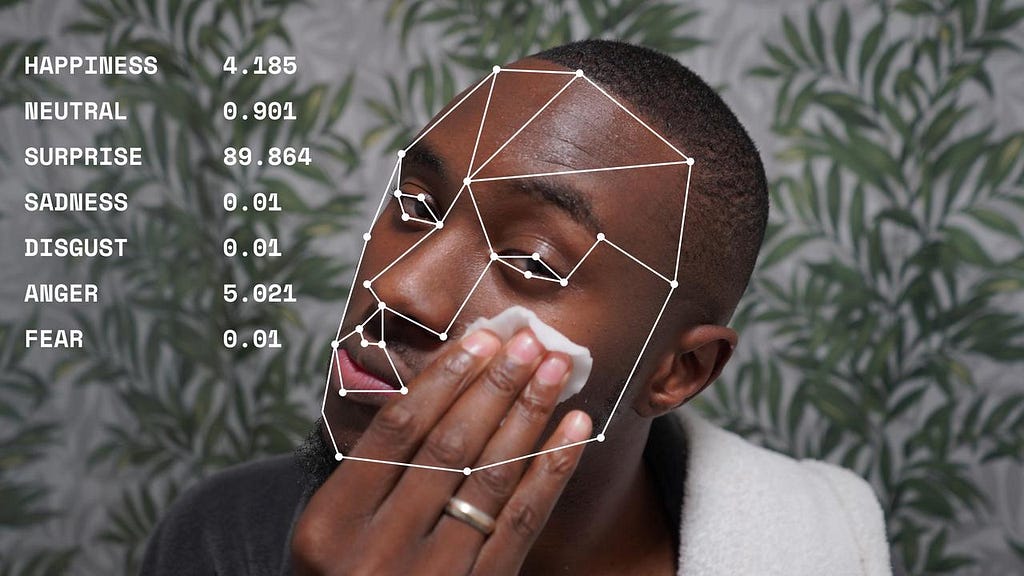

First of all, emotional data never exists in a vacuum. Quite to the contrary, it is inferred by processing large quantities of (sometimes more, sometimes less, but always) personal data. It is deduced by analyzing our health data such as blood pressure and heart rate, as well as our biometric data like eye movements, facial scans, or voice scans. And by combining all these various data points used, it is in fact possible to identify a person.[3] Even the GDPR testifies to this fact by explaining already in the definition of personal data that indirect identification can be achieved by referencing “one or more factors specific to the physical, physiological, genetic, mental, economic, cultural or social identity of [a] natural person.”[4]

The easiest examples are, of course, various emotion recognition systems in wearable and personal devices such as the ones Jane has, where the data is directly connected with her user profile and social media data, making the identification that much simpler. However, even when we are not dealing with personal devices, it is still possible to indirectly identify people. For instance, a person standing in front of a smart billboard and receiving an ad based on their emotional state combined with other noticeable characteristics.[5] Why? Well, because identification is relative and highly context-specific. For instance, it is not the same if I say “I saw a sad-looking girl” or if I say “Look at that sad-looking girl across the street”. By narrowing the context and the number of other possible individuals I could be referring to identification becomes a very probable possibility, even though all I used was very generic information.[6]

Furthermore, whether someone is identifiable will also heavily depend on what we mean by that word. Namely, we could mean identifying as ‘knowing by name and/or other citizen data’. This would, however, be ridiculous as that data is changeable, can be faked and manipulated, and not to mention the fact that not all people have it. (Think illegal immigrants who often don’t have access to any form of official identification.) Are people without an ID per definition not identifiable? I think not. Or, if they are, there is something seriously wrong with how we think about identification. This is also becoming a rather common argument for considering data processing operations GDPR relevant, with increasingly many authors taking a broad notion of identification as ‘individuation’[7], ‘distinction’,[8] and even ‘targeting’.[9] All of which are things all of these systems were designed to do.

So, it would appear that emotions and emotional data might very well be within the scope of the GDPR, regardless of whether the company processing it also uses it to identify a person. However, even if they aren’t, the data used to infer emotions will most certainly always be personal. This in turn makes the GDPR applicable. We are not getting into the nitty gritty of what this means or all the ways in which the provisions of the GDPR are being infringed by most (all?) providers of emotion recognition technologies at this point. They are after all still busy arguing that the emotional data isn’t personal in the first place.

3. Does It Even Really Matter?

We’ve all heard the phrase: “You know my name, not my story.” We also all know that that is very true. Our names (and other clearly personal data) say much less about who we are than our emotions. Our names can also not be used for the same intrusive and disempowering purposes, at least not to the extent that recognizing our emotional states can be. That is also why we are in most cases not being identified by the providers of these systems. They don’t care about what your name is. They care about what you care about, what you give your attention to, what excites or disturbs you.

Sure, some of them sell health devices that then infer your emotions and psychological states for health purposes. Just as scanned Jane, many people probably buy them exactly for this purpose. However, most (all?) of them are not doing just that. Why let all that valuable data go to waste when it can also be used to partner up with other commercial entities and serve you ultimately personalized ads? Or even save you the trouble and just order the thing for you. After all, the entity they partnered up with was just one of the solid options that could have been chosen for something that you (presumably) need.

Finally, for these purposes and especially when considering other, non-health-device, emotion recognition systems, it is also increasingly irrelevant to recognize specific emotions. Making the whole, debate on whether ‘reading’ emotions is a science or a pseudoscience to a greater extent irrelevant. As well as the previously discussed question of what emotions are, because then we have to go through the same mental exercise for any state they eventually end up recognizing and using. For instance, nowadays it is much more important to put you somewhere on the PAD (pleasure-arousal-dominance) scale.[10] This then suffices to asses your general attitude towards a particular information, situation, ad, you name it. Is it causing positive or negative sensations, is it capturing your attention or not, is it making you proactive or receptive? And that is finally enough to serve you with just the right ad at just the right time. If you are even still being served an ad that is and not just getting a delivery to your door.

4. Final thoughts

So, what are emotions? They are a lot of things. They are internal perceptions of our current state and environment. External representation of those perceptions. And computational readings of those representations. This long-winded road also makes them a type of data. Data that can in some cases, when combined with other data points or used in narrow enough contexts, be personal. And this holds true, irrespectful of what emotions are in a psychological sense. Lest we wish to get entangled into questions of what attention and excitement are. Or have system providers sleazing out of the GDPR scope by claiming they don’t actually recognize emotions but rather simply track user reactions across the PAD scale.

This conclusion then makes any single entity recognizing and using data obtained by ‘reading’ our facial expressions and bodily cues also responsible for what it does with the collected data. With the bare minimum of its obligations lying somewhere between meaningful transparency with full disclosure of purposes for which the data is collected and including an easily accessible possibility to object to the processing. This is currently far from common practice.

Even when it comes to Jane’s all too smart devices, mentioning how the data is collected, used to predict her emotional states, and then make decisions based on those states somewhere in the Terms of Service does not mean transparency can be ticked off the list. And where are we then from having any type of influence over these data flows that we constantly emit into our orbit for our devices to process?

Finally, when other, non-personal devices are considered, the situation gets even worse, of course. Be it mood-based social media algorithms or smart billboards, they all process personal data to generate some more (as we have established) personal data and use it to influence our behavior. Being fully mindful of the fact that it is difficult to fulfill the transparency requirements when individuals are walking past a billboard or scrolling social media, they are still requirements. Not just helpful recommendations. Envisioning novel approaches for achieving meaningful transparency is a MUST. And so is thinking about emotions and emotional data in a robust manner, free of psychological finesses and discussions. Otherwise, we might soon lose all that is left of our power to make decisions.

[1] Aristotle, Rhetoric, 350 BCE, translated by W. Rhys Roberts, available at https://classics.mit.edu/Aristotle/rhetoric.2.ii.html.

[2] P. Ekman, Darwin’s contributions to our understanding of emotional expressions, Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2009 Dec 12; 364(1535): 3449–3451. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2009.0189, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2781895/ .

[3] L. Sposini, Neuromarketing and Eye‑Tracking Technologies Under the European Framework: Towards the GDPR and Beyond, Journal of Consumer Policy https://doi.org/10.1007/s10603-023-09559-2

[4] Article 29 Working Party, Opinion 4/2007 on the concept of personal data, 01248/07/EN WP 136, https://www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com/Documents/Privacy-European-guidance.pdf p.32, 38; Judgement of 19 October 2016, C-582/14 Breyer, ECLI:EU:C:2016:779, para.32.

[5] J. Metcalfe, A Billboard That Hacks and Coughs at Smokers, Bloomberg, January 17, 2017, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-01-17/a-smart-billboard-that-detects-and-coughs-at-smokers?embedded-checkout=true

[6] Article 29 Working Party, Opinion 4/2007 on the concept of personal data, 01248/07/EN WP 136, https://www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com/Documents/Privacy-European-guidance.pdf p.13.

[7] Vidal-Hall v Google, Inc. [2015] EWCA Civ 311

[8] P. Davis, Facial Detection and Smart Billboards: Analysing the ‘Identified’ Criterion of Personal Data in the GDPR (January 21, 2020). University of Oslo Faculty of Law Research Paper №2020–01, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3523109 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3523109

[9] N. Purtova, From knowing by name to targeting: the meaning of identification under the GDPR, International Data Privacy Law, Volume 12, Issue 3, August 2022, Pages 163–183, https://doi.org/10.1093/idpl/ipac013

[10] Kalinin, A., Kolmogorova, A. (2019). Automated Soundtrack Generation for Fiction Books Backed by Lövheim’s Cube Emotional Model. In: Eismont, P., Mitrenina, O., Pereltsvaig, A. (eds) Language, Music and Computing. LMAC 2017. Communications in Computer and Information Science, vol 943. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-05594-3_13, B. J. Lance and S. Marsella, The Relation between Gaze Behavior and the Attribution of Emotion: An Empirical Study, September 2008, Proceedings of the 8th international conference on Intelligent Virtual Agents

What are Emotions, Legally Speaking? And does it even matter? was originally published in Towards Data Science on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Originally appeared here:

What are Emotions, Legally Speaking? And does it even matter?

Go Here to Read this Fast! What are Emotions, Legally Speaking? And does it even matter?